The strange thing is that such a toy, which would probably be made in Germany, has a lacquer varnish or paint on the metal parts which, when heated, gives off the sweet Friars balsam-like scent - and yet I never had an engine of this kind. I don’t know where I would have seen one.

Many years later, towards the end of the Second World War, when metal toys were a dream of the past, I saw the steam engine, looking rather battered, and repaired with clumsy soldering, on a shelf in a toy shop in Weymouth. I was almost sick with excitement and could hardly summon the courage to ask whether it was for sale or just a decoy or museum piece. It was for sale, and was said to be in working order. I purchased it, for my son.

My bedroom was a small long room, as such rooms usually are which are situated over the hall or passage leading to the front door. The wall paper was the same as the nursery except that the cornflowers were pink not blue.

Lying in bed, waiting for or warding off sleep, I would take a pencil and start filling in certain shapes in the design. Sometimes the pencil would go right through the paper; evidently there were holes in the plaster underneath. This invited me to feel and prod with my fingers along the wall behind the bed until the corner made by the chimney breast was reached.

Here the paper was tightly stretched across the angle and, when my thumbnail sank in, the delight in running it down the corner, the paper tearing with a brittle feeling all the way down, was intense.

Then I feel further along the width of the chimney breast and here in the corner that seems to have a hollow at each side of the slightly rounded angle. I press again with my thumb nail and in it goes! I run it down the ridge on either side with the same sensuous feeling. But now we explore a little further. The light is fading and suddenly the room is faintly illuminated by the street lamp outside our gate. My fingers explore the faceted cover of the bell pull. It is cool and pleasant, being made of china. It unscrews and inside I can feel how the lever is on a spring and a wire disappears down into the depths of the wall where it must go by some strange route down to the kitchen to shake or ring a bell hung in a coiled spring with a number on it. I have stretched as far as I can reach so I retrace my wanderings along the wall, back to the recess. I run my thumb down the slit in the paper again. I encounter a deeper hollow, evidently a hole in the plaster. Bits drop down behind the wall paper and some fragments seem to drop further and further. Where do they go to? There have been strange scratching sounds lately behind the skirting board. There must be passages running all round the room, lots and lots of them.

Strange shadows are moving around the ceiling, reflections of people passing in the street; they frighten me rather. I listen to the footsteps and look at the shadows upside down. I cover myself up completely with the sheet and blankets but still the walls of the room impress themselves on my vision. The door in the shadows seems to get taller and taller; it slowly opens. I am terrified but keep quite still. I watch and Mother looks round the door to see that I am alright but she must be very tall; her head appears near the top of the door and what is she wearing on her head? A busby! I pretend I am asleep.

Next morning at breakfast I thought Mother might still be wearing the strange head-dress and I felt self-conscious and shy. I glanced quickly at her and saw she was her usual self. I ate my breakfast in a somewhat abstracted frame of mind. I was expecting, no doubt, some explanation for the performance the night before but none was forthcoming.

Scented soap and baby powder, the warm smell of drying towels on a small clothes horse, babies' nappies, and the curious smell of babies themselves. The high brass fire guard on which more towels and baby clothes are spread out - and the kitchen is a perpetual festive scene with banners and bunting.

The baby is always bathed in a small tin bath in the nursery. I remember myself being bathed in it and swallowing water sucked from the enormous sponge. Now another sister has taken my place and I am promoted to the big bath in the bathroom. I could swim round and round in the big bath, as I was very small and flexible. One of the few things which made Mother rather cross was the amount of water splashed on to the bathroom floor. It came through the ceiling in the kitchen below. But the large bath had one disadvantage - it had a torture chamber at one end, consisting of a wateringcan-like rose near the ceiling and cupboard doors which folded across the enclosure at the head of the bath. The condensation of steam in the rose made it drip cold drops of water so, when swimming round the bath, I would usually be completely under water while taking the turn at the head end. Once when I was in the bath our lady help, no doubt in a playful mood (or was it vindictive?) turned the cold tap operating the shower. The screams that followed convinced Mother that something frightful had happened and brought her to the scene in great haste.

Watching my sister being bathed in the nursery had a good deal that was amusing but perhaps the fact that I was no longer the focus of attention for the grown-ups led me to experiment. I found, much to my pride and delight, that I could walk backwards. 'Look! Look! Me walking backwards!' I shouted, and indeed I was but it ended with me on top of my sister in the bath and much splashing.

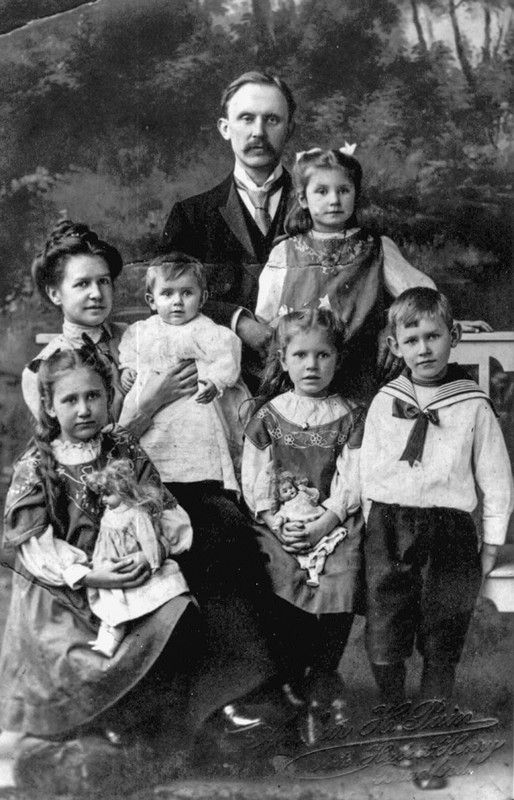

There was a strange custom, I believe, in Edwardian days of dressing very small boys in a short skirt or kilt. On my third birthday I was promoted to knicker-bockers. I stood at the top of the stairs while Mother and the rest of the household looked up at me. It was a moment of triumph. Mother asked me whether I had noticed the pockets. No, I hadn't. I plunged my hands into them and one of them closed round a small object. It was a threepenny bit!

There is something a bit theatrical about the turn at the top of the stairs and the curtains with bobbles on them tied up at the bottom. For, at about this time, I had my first girl friend to tea. Mother looked up the staircase and saw us both appear hand in hand at the top and then, to her consternation, we somersaulted down the stairs together, arriving at the bottom none the worse for the performance.

In the hall there was a gas bracket. The ironwork which held the glass shade itself was of elaborate scroll work and the shade itself was a cloudy green and irregular of surface with a wavy frill round the top. Father had a wonderful lamp in his study or consulting room which could be pulled up and down. He also had a revolving chair and a revolving bookcase; most exciting of all, was a basin which tipped up and poured the dirty water into a tank below. The water supply came from a tank above, through a tap which operated when pulled out at right angles and the water stopped when it was pushed back again. The complete cabinet was finished in mustard yellow varnished wood.

We were not often allowed into Father's consulting room. It had a heavy curtain on a rod behind the door, presumably to make the room more sound and draught proof. There was a couch or settee also draped in a heavy dark rug with tassels round the fringe. There was a glass cupboard full of surgical instruments, some made of shiny metal; others had strange rubber bulbs and tubes. There were syringes and squirts and glass measures and flasks, all sizes of glass stoppered bottles, some being blue or green containing powders, pills and liquids. There was cotton wool in blue paper wrapping; there was a retort and a methylated spirit lamp under it and some strange-looking tongs for holding things in a flame. Over the mantelpiece was the picture to be found in every doctor’s house, The Doctor by Luke Fildes.

But round the fireplace at a more visible level were some miniatures of Father’s ancestors. One fascinated me particularly; a youngish man looking rather like a portrait of Mozart with broad forehead and bold eyes. One side of the room was entirely taken up by a huge bookcase with glass panelled doors, behind which stood the most impressive binding of medical books, mostly German; also a number of volumes of natural history which it became a special treat to have out on certain Sundays when Father would also get out his beetles, of which he was a keen collector. There were many hundreds of varieties in cases which he set and mounted most carefully. In a corner there was also the letter chart for testing eyesight and, last but not least, the large, roll-top desk.

I think that on the rare occasions of our being allowed in this room, the desk and it contents attracted us most. There were two leaves that pulled out over the drawers at either side and it was a treat to be allowed to sit on a high stool and be given an old envelope to draw on at one of these. But there was an array of monsters on the desk which were both repellent and fascinating. There was a skull resting on cross bones. The top of the skull was a lid and when opened it revealed an ink well. There was also a paper weight of skulls and a seal with a hairy back which was a pen wiper. There was a paper knife with a snake handle. A stethoscope was folded up and lay on the desk and also a circular mirror with a hole in the middle. This became a rather terrifying instrument when strapped on to Father's forehead so that the light of a lamp reflected in the mirror was shone into one’s throat, while Father’s eye gazed through the hole in the middle. He would then raise it on to his head and write or do other things with the strange headgear on. A large microscope also stood on the desk looking most dignified and important in its proportions, perhaps somewhat resembling some new manifestations in sculpture.