In the Summer Term my Grandmother (Father’s Mother) came to see me at school on her way to Germany. She was short and dumpy with a considerable beam. We were naturally curious about each others' parents and other relations. I was surprised at some of them; anything less like my idea of a parent I couldn’t imagine. There were loud and hearty ones, overdressed and flamboyant. They came in large cars. There were hard and calculating pale creatures who I could not imagine having any domestic life at all. Some of the boys were excellent mimics and while undressing in the dormitory at night they gave of their best and experiments were tried out.

There were several members of the female staff besides the Headmaster’s wife, who were beamy. They all looked rather like ships’ figureheads emerging from a rotund hull as they leaned forward. Or such was the effect as they walked. My Grandmother was another one to add to the collection and several bright spirits speculated on the progress of these ships when negotiating the narrow passage past the Headmaster’s study. These sparks then stuffed pillows and garments into their pyjamas fore and aft and waddled down the dormitory like a number of ducks. My neighbouring friend also invented things that 'Katy Did' at home and at school.

The satirist was gaining on the poet, for in discussions during the past year we had talked about our future. I said I was going to be a doctor and he went one better by saying he was going to be a medical missionary. But now I had ideas of being an artist. The pattern forecast was correct for he became a poet on themes of nature and birds which gave way to satirical moods.

We talked over our plans for the holidays and counted the days left at school. I can hardly remember anything more joyous than seeing my own cabin trunk coming out of store and the matron starting to pack. But I was dismayed to hear from Mother that we were all going away for a month on holiday. I only wanted to get home and see Bradford and its landscape and all the familiar things. The trees and hedges of Hertfordshire oppressed me. They looked overblown and weary, the hedges were dusty and the houses looked more like cheap dolls’ houses than ever. The journey home was exhilarating and Little and Humphries escorted me and actually bought me a meat pie at Melton Mowbray where they always sold them on the railway platform.

The holiday near the sea in Lancashire was overcast by all sort of rumours after war was declared. Mother taught us some new hymns and Father was worried about his Mother in Germany. When we got back to Bradford recruiting for the Bradford Pals Battalion was in full swing and those already enlisted marched up Manningham Lane in civilian clothes but perhaps wearing a belt or puttees to show they were in the army. Stationers’ shops were full of postcards of the King and Queen and Kitchener. Gradually they expanded to include Generals French and Allenby and others.

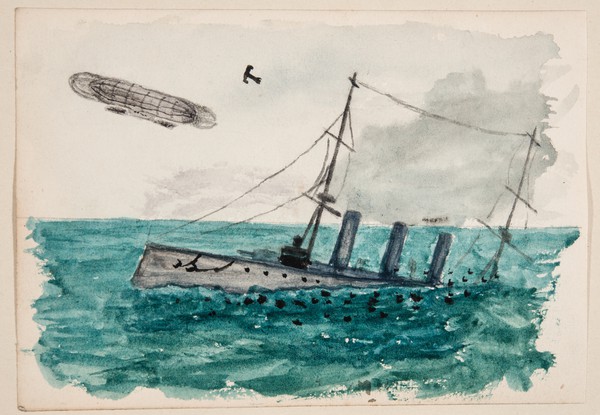

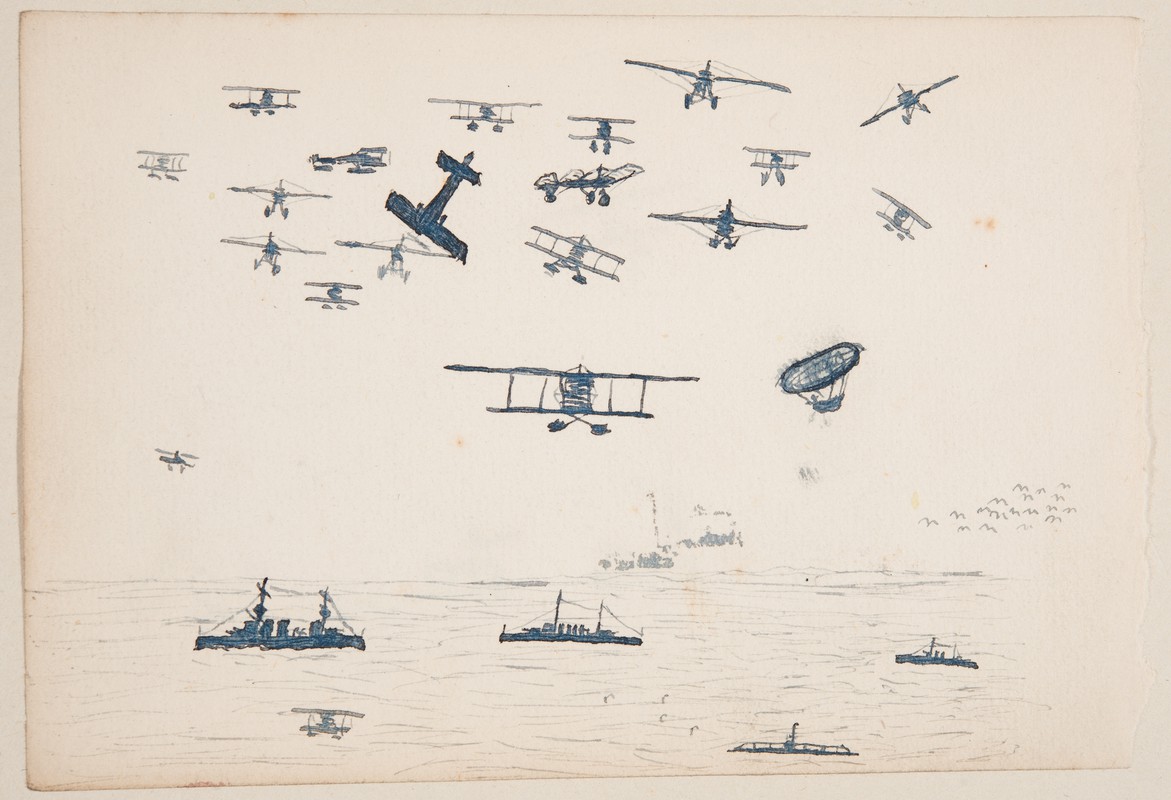

When I got back to school there was a new feeling in the air and not a good one either. That I had German relatives was well known. Two cousins were in the German army. It was hinted by boys that they didn’t know why I was allowed to be at school. They fastened on my second name which was Ernst as proving the fact of my being really German, if my surname hadn’t done so already. If I pronounced the name of German composers correctly I was looked at with great suspicion. Small boys argued among themselves about the status of the fathers and uncles as officers in the army. They also thought they were quite strong enough to go and fight too. They collected military buttons and cap badges and organised pitched battles with acorns as ammunition. Wild stories were bandied about and thought to be true, such as the train load of Russian soldiers coming to our assistance with the snow still on their boots. The death of Kitchener at sea led to all sorts of speculations about his really being in enemy hands.

Atrocity stories were encouraged, so it seemed, as members of the staff were drawn into conversations of this sort in lessons and at mealtimes. The Headmaster fancied himself as a master tactician and at morning prayers would drag in some argument of his own concerning military tactics. Even the dreaded Headmaster's Scripture became a discourse on strategy. He also informed us as to how the strangely spelt Russian and Polish names should be pronounced, often incorrectly as I subsequently found out.

Boys of twelve and over were expected to join the Cadet Corps and I remember a sergeant major from some local regiment coming to give instructions to these boys in bayonet practice. With charming humour he demonstrated how 'once you’ve got your bayonet in, you have got to get it out again' which apparently was not too easy unless you had got it in as instructed by a man of experience like himself.

Then the Belgian refugees came. The Headmaster had a bright idea that if we had a 'starvation dinner' once a week the funds saved would go to their relief. So we had to have dry bread and cheese. Whether our parents, who paid for our keep (which was scanty enough) were asked for their approval I very much doubt.

One day in assembly the Headmaster gave a stirring account of heroism on the field of battle. When he had left us all standing and waiting to be dismissed, an unheard of incident occurred. A housemaster who bore a German name, walked from his place among the rest of the staff and mounted the dais and in simple words told of the heroism of a German soldier. 'Remember,' he finished, 'heroism is not confined to one side.'