One term we came back to find ourselves in a humiliating position. On the locker by our beds was a printed timetable for a week with spaces to fill in every night and morning. I have washed. I have brushed my teeth. I have said my prayers. I have read the Bible (state chapter and verses). I have been to the W.C. and so on.

More humiliation when petty thefts broke out. A fountain pen or something was missing. So without warning, the lower school was sent to the assembly hall and suffered the indignity of being searched by prefects. The contents of our pockets were put into paper bags and confiscated.

One day the Headmaster appeared at assembly in a towering rage. It was concerning a door that had been found off its hinges. 'Some boy has done this. Only a boy with a vicious nature could have done such a thing and not reported it. It must have been done deliberately' etc., etc. He expected this boy to own up or else the whole school would be punished. The usual form of blackmail indulged in by schoolmasters who are diplomatic failures. The attack had been a fierce one and we all felt sore about it. But oddly enough the time limit expired and we heard no more about it officially. And then it gradually leaked out that old Daddy, the librarian and classics master had done it. He had one of the most tattered gowns ever worn and he would roam the corridors with the tatters flying, humming some little tune to himself, his bright eager eyes fixed in space, his spectacles awry and tied together with bits of wire and sticking plaster. He had caught his gown in the door handle and the flimsy door had come adrift. The Headmaster never mentioned the subject again to apologize for his accusation.

Part of a questionnaire about smoking and bad language ended in a regular field day; he must have been fighting fit for he caned over seventy boys in one day.

The sixth formers were the only privileged persons. There were only half a dozen or so of them but they had a room to themselves. Other boys had no privacy whatsoever. There was the library but even here small boys were hunted down by prefects who thought that moving chairs and desks about was a more fitting occupation than reading. I started to read Holmes' Life of Mozart but had no chance to finish it. I also discovered something about Leonardo da Vinci and one day after an arithmetic lesson, I spoke to the master about it. He looked at me with an expressionless face and remarked that he could not understand that I could be interested in such things and not in mathematics. He invariably gave me shocking reports and many years later my younger sister met him and informed him of my progress. He remarked that he always thought I was promising. Mother laughed when she heard this as she remembered the reports.

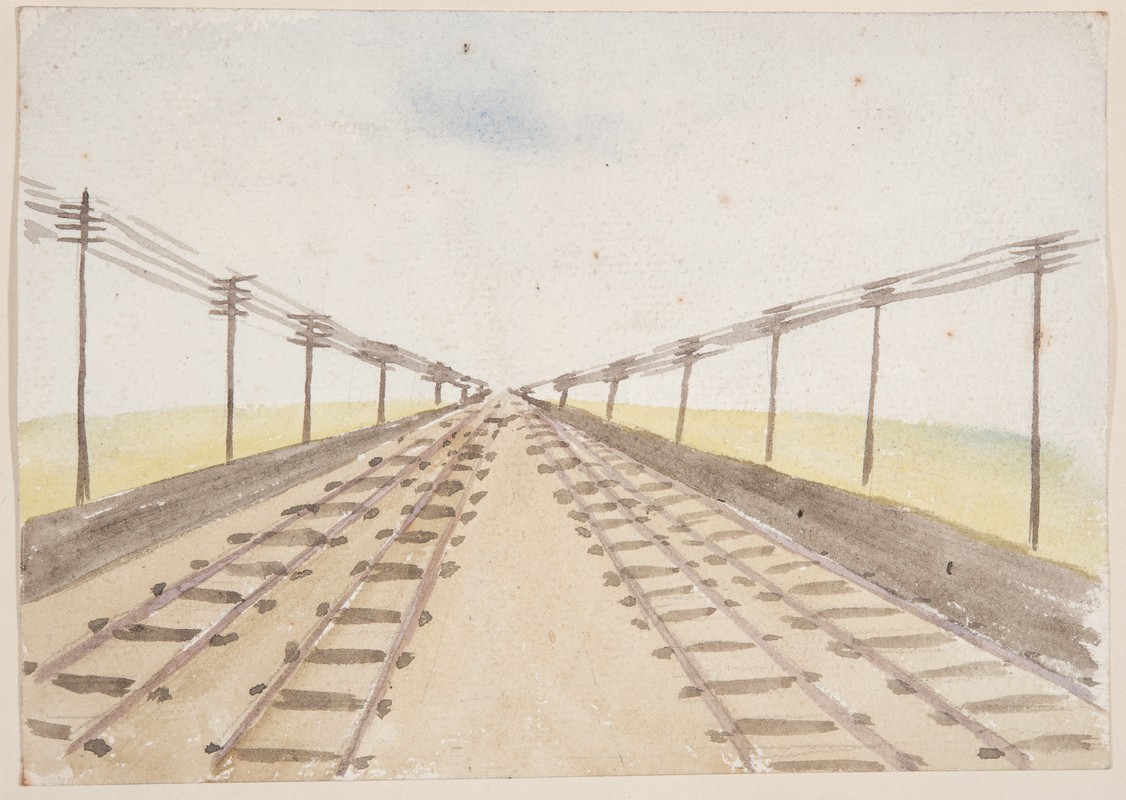

Having no play box meant that my paint box and drawing books and other treasures were in a locker with no lock. The result was that other boys made off with them and if they were returned they were in a useless condition. My violin which was a valuable one was also mistreated, and my only effort to keep a pet in the form of a water-beetle or two in a jar on the windowsill was ended when I had to go into the sanatorium for a few days. I found it had been emptied away when I came out. There were no animals of any kind on the school premises except a cat or two in the kitchen and boiler house.

I made a tremendous effort with my schoolwork but even so could not keep up with others younger than myself who appeared to take it in their stride. The effort sometimes led to a sudden necessary relaxing and my thoughts would be far away. I was sometimes called 'the dreamer' and several times our French mistress caught me out. She turned to the rest of the class and explained to them that I was dreaming of paint boxes and painting. I am not sure how she discovered my weakness unless the drawings of flies and beetles in my exercise books, all shaded so as to look as real as possible, had given her some clue.

There were some pictures in the assembly hall. They were prints of old fables, some of them illustrating the life of the saint who was the patron Saint of the school. I tried to get a good look at them when we were moving chairs about. I liked them very much but did not discover until years later that they were by Carpaccio.

The impossibility for the boys to have hobbies under these conditions naturally led to bullying and playing about in an aimless way, such as throwing chairs over in the laboratory and being a general nuisance.

It began to dawn on my harassed parents at last that everything was not well. They had enquired about my health and weight but had always met with evasive answers. At length under pressure, it was revealed that I had gained hardly a stone in weight in the four years I had been there. I was just under five stone at fourteen years of age.

My requests which had been frequent to leave the school were granted. On letting this splendid news be known, one mistress said I would probably turn up next term like a bad penny. I replied, 'I hope not'. Father came down to fetch me and had a session with the Headmaster. I asked him what had been said. He replied that the Headmaster appeared to be so nervous he could get nothing out of him. In the train going home Father expressed the feeling that I might regret the change but I said I wouldn’t. 'Well, we shall see' he replied. There were no regrets.