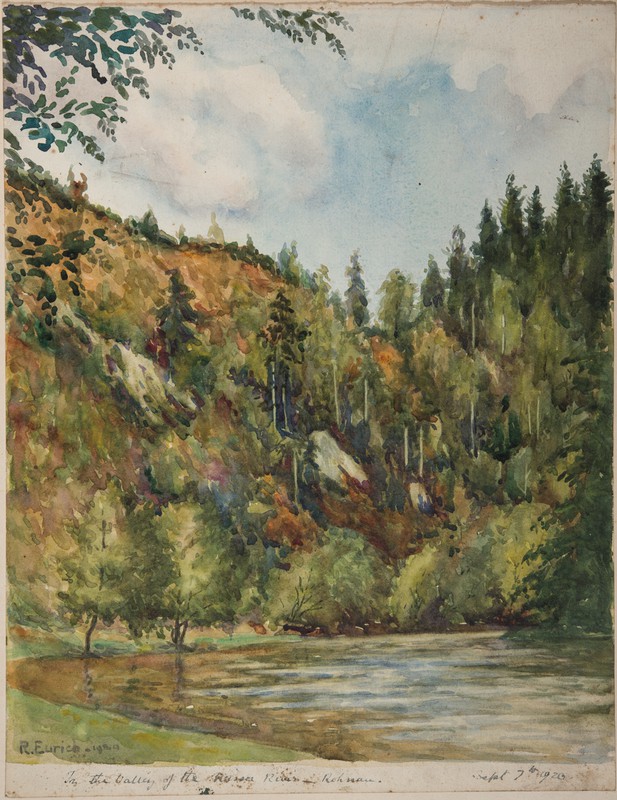

Valley of the Neisse River - Rohnau (1920)

The Valley of the Neisse River (1920), Rohnau, probably painted on the spot

During the next few months I went on painting whenever I had any time. Mr. Pearson continued to take an interest in my work and Father had to face the fact that I was perfectly serious about being a painter. But his interest in heredity came to the rescue. He had in his possession two miniatures, portraits of ancestors executed by a relation of ours on his side of the family in the middle of the last century. We also had a chalice decorated by him with figures of the twelve apostles. When it was fired it developed a crack so that is how it remained in the family, another one being substituted for the church. When he was thirty years of age August Eurich decided to leave Germany for America with his wife and baby son. Unfortunately he died on the voyage and his wife earned her living by teaching music. Her son, Ernst became the father of Richard Eurich who carved the small boat for me, referred to in an earlier chapter. So Father took some pleasure in what he considered as inevitable as he did when my brother decided to take holy orders, there having been many clergymen on both sides of our family.

So in the summer of 1920 he decided to give me a year’s trial at the Bradford School of Art. I entered for a scholarship, being asked to draw a plaster cast of a lion’s head. I was granted the scholarship and so the end of my schooldays was drawing near, much to my satisfaction.

Father had decided to go to Germany to see his mother and her sisters, who had come through the war looking thin but well. My eldest sister was going with him but it was an afterthought that I should go too. The people looked starved though the wealthy classes could get what they wanted. Father warned us that we would not be able to eat as much as we were used to. We had some good bacon and egg at a Berlin hotel but when we asked for coffee the waiter enquired whether we wanted just coffee or bean coffee. The latter was the genuine article at a price. Coffee was a substitute probably made of some tree bark. We tried it and were agreeably surprised by its flavour and so we found throughout our stay that substitutes were very general. The upholstery in the railway carriages was a mass of patchwork of different materials and in the mornings I heard a strange noise in the streets. It was men going to work on their bicycles. But they had no rubber tyres. The wheels had a fringe of metal spiral springs attached, which acted as shock absorbers.

We visited the picture gallery. I remember nothing but some large nineteenth century religious pictures including Christ among the Doctors by Hoffman. It was all very depressing.

From Berlin we travelled down to Dresden and from there to Zittau. One or two people hearing us speaking English joined in the conversation wanting to air their knowledge of the language. They were puzzled by the anglicised names of towns we used, even Berlin stumped them for a bit until at last it dawned on them and they exclaimed 'Ach, Bearleen!' I noticed again as we approached Zittau the old sour smell which I associated with it.

Our meeting with the old folks was touching in the extreme. It was obvious that Father had always been a great favourite with them. Mother said they all cried when he married her! They admired our clothes and shoes and told us of the wonderful new suit a friend of theirs had purchased. He was a cloth merchant and believed in having the best while he was about it. It was quite a family affair and the suit was very much admired. One day he happened to be out in the rain for a while and next day he discovered that he could hardly sit down, his trousers were so tight they threatened to split. The ‘cloth’ was made of paper!

We noticed there did not seem to be any children under five years old. We only saw one perambulator with a baby in it and this obviously belonged to a wealthy family. The boys in the park were playing football barefoot and clothing was patched and tied up with string.

When the first emotions of reunion had begun to die down a bit we started to entertain ourselves, Father by hunting for beetles and I by drawing and painting. I went to the park several times and became completely absorbed in my efforts. One day I heard a soft sound like something falling near me and I saw out of the corner of my eye, a squirrel searching the ground for food. I kept quite still as it came near me and examined my shoes, as people had done. It wandered about under my seat performing comic antics. Some movement of mine must have startled it as it suddenly shot up a tree trunk and appeared round the other side taking another look at me and making chattering noises. Another time a swallow came and perched on the toe of my shoe. I was reminded of Constable finding a mouse in his pocket. This intimacy with nature is one of the rewards of patient work and observation out of doors which I prize very highly.

During the early months of the Second World War I was drawing on some flats at low tide when I had that feeling that I was being watched. I resumed drawing for a while but still felt conscious that I was being observed so I looked round carefully and then saw a face bobbing up and down on the edge of the scar I was standing on. It was a young seal absolutely consumed with curiosity. It looked very much like an inquisitive neighbour hanging over the garden fence and about to offer some friendly advice.

One day we took the train, which we called the Bimmel Bahn because it had to constantly ring its bell as it passed across streets, and fields where cattle strayed about. Its coaches were rather like single decker trams. The orchards and allotments we passed through were a wonderful sight, the trees being weighed down with fruit; in many cases ladders were propped under the boughs to support them. The allotments had great giant sunflowers among the plants. I had never seen them before. The prints of Van Gogh’s paintings had not yet come to the market. The peasants in the fields waved to the train as it went by. It did not run as often as it used to owing to the shortage of coal. That in use looked rather like chocolate and gave off a very heavy black smoke. One of the men we passed stood like some heroic figure with his hand resting on a spade; his shirt was open down to his trousers and his chest displayed the blackest and thickest pelt of hair I had ever seen.

The train took us to the foot of the Hochwald, a small mountain completely covered in pinewoods. There were some old ruins on rocks standing out above the trees and at the summit a tower. The quietness and the warm smell of pine surrounded us as we climbed to the top, the sunlight piercing the trees here and there with shafts of light dappling the thick carpet of pine needles. The view from above was amazing. The alternate shapes of pinewoods and fertile land undulated gently as far as the eye could see in the haze, a few villages looking just like those depicted in the backgrounds of Durer’s engravings. I made a rapid water colour sketch which developed blots and pools of colour all running together, I was so anxious to get the excitement I felt on to the paper. As we started our homeward journey down the hill-side we found an adder which Father played about with for a while making it bite his stick so that the poison came out of its ducts.

In a particularly thick part of the forest I decided I wanted to make another painting but while I was doing so it started to rain. The gentle sound of the drops was most eerie in that silence. Father loved these surroundings that were like some of Gustave Doré’s illustrations to fairy tales. He carried an umbrella with him into which he shook beetles from bushes and then picked them out and examined them at leisure. So now he came to my rescue, holding the umbrella over me and in particular over my paper while I worked until the painting was finished. He was rather proud of this joint effort but I was not at all happy about it. No doubt I did not as yet realise that an artist is never satisfied.

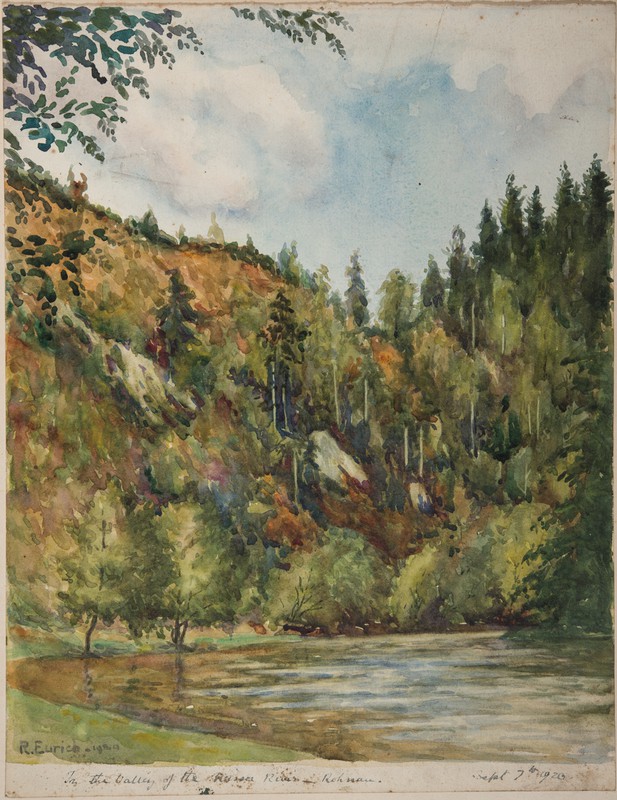

Valley of the Neisse River - Rohnau (1920)

The Valley of the Neisse River (1920), Rohnau, probably painted on the spot

Another day we penetrated into Bohemia and I sat down to paint a bend in the river Dneiser. It was all lazy sun and lush growth with cows browsing peacefully and a young man with a straw in his mouth leaning on a long stick or crook dreaming as he gazed across the landscape.

We spent another day in Dresden. We went there to see another of Father’s 'Aunties' and also we made time to go to the Picture Gallery. It was inevitable that we found ourselves in the hushed padded atmosphere of the room that houses the Sistine Madonna of Raphael. The Germans adore this Christmas card In Excelsis. It seems to have all the necessary ingredients and accordingly a print of it hung in every home. I couldn’t stand this room and was glad to get out of it. Next we looked at Holbein’s Madonna with the donor’s family. I did not care for it very much but liked the colour scheme of black, red and gold, refreshing after the blues and greens of Raphael. Nearby was a tiny Crucifixion by Durer. I was disappointed. It too was almost like a greetings card, but near it I found some plain oak frames with simple white mounts containing watercolours of landscapes. I looked from one to another. They were so fresh in their vision, so straightforward and uncompromising in their presentation. I would have said they were modern if I had known any modern landscape painting. Father came up to me and I saw an amused smile on his face. I suppose mine was faintly puzzled. 'Well' he said, 'Do you know who they are by?' I confessed I hadn’t an idea. 'They are by Durer' he replied and so they were. But I almost forgot them after I had been in the next room. Here I remember three paintings, which is quite enough to take away from one visit to a gallery. There was Rembrandt’s Sacrifice of Maurah. It was a very large picture full of mysterious spaces. But I have never seen that telepathic sense conveyed so well as in the old man here, praying with all the concentration he is capable of, leaning over towards the woman at his side as though to help her as she is certainly only a novice.

The Rembrandt picture of the old woman that caught Richard’s attention in Dresden

The second picture was the finest. An old woman weighing money, also by Rembrandt. The effect of the paint in the picture I shall never forget. The third picture was Vermeer’s Courtesan, brilliant in its red, yellow and white, a masterly and unconventional design but almost cheap and flashy beside the retiring richness and timelessness of Rembrandt’s Old Woman. It was unfortunate that I could not go up to this picture and examine it as I should have liked as there was a greasy looking old man making a copy of it and he munched all the time, his bushy moustache elevating itself at every upward thrust of the jaw. It is a pity that I cannot separate the two images in my memory.

I once attended a piano recital given by a famous pianist. Unfortunately there was a woman sitting next to me who had a most revolting scent about her so that I associate this with the pianist to this day. Father gave me as a memento of this visit a small paperback book on Durer. It had not got any of the landscapes in it but it introduced me to Melancolia, also Knight, Death and the Devil and The Four Horses of the Apocalypse which was quite enough to go on with.

Mr. Stott was delighted when he heard our address in Germany was Mozart Strasse and wrote me a letter asking me to see if I could get him a special edition of Bach’s Forty Eight Preludes and Fugues that he wanted.

Our stay came to an end. While waiting in the train after having landed in England again I drew a picture of the boat on the quayside from the window. My sister made the odd remark that she couldn’t understand why one who could draw so well couldn’t spell.