Portland (1922)

View across to Portland in typically murky weather

From time to time I was invited to go to Weymouth to stay with my cousins who fortunately owned a sailing boat, and Weymouth Bay and Portland Roads became as well known to me as the moors at home. The shape of Portland against the sky never alters: Chesil the bay presents the same magnificent sweep from any vantage point and the Chesil Beach stretches from Portland for eighteen miles, a shallow crescent of shingle facing the rollers from the Atlantic. No boats can be drawn up on this desolate shore which has claimed so many wrecks through the ages.

I always made drawings of ships, battleships and any incident that took my fancy but it was not until now that I took my paints and began battling with the elements in the effort to study the sea. By this I mean the structure of water; not just the sea as a blue background with landscape or harbours as the main feature. When out sailing I never tired of watching the formation of the water breaking against the sides of the boat, and the wake in particular with all its diverse currents interlaced with broken water, framing wonderful patterns expanding and contracting as the distribution of weight shifted endlessly. I found that watching the water through a shape in the rigging of the boat intensified the forms of waves and enabled me to fix my attention on a certain area instead of dissipating the vision over a wide expanse in which the light and colour were dominant.

Portland (1922)

View across to Portland in typically murky weather

My earlier visits to Weymouth were spent mostly sailing and walking. The walk round Portland always afforded the opportunity for making drawings and mental notes so valuable to a painter, not necessarily at the moment, but often years afterwards, when just a few lines with a pencil and written notes on colour and the weather bring back with remarkable vividness the occasion and the mood. Sometimes one is tempted to think, on seeing some magnificent scene, that the camera is the only means of making a record to remind one of its grandeur. But this is not so to a painter. The mere act of putting a pencil to paper and looking and trying to record something seen means that one has been in real contact with nature, and viewing an old sketchbook with only the slightest of drawings in it, makes a flash back in the memory which a photograph album is powerless to do. The act of pointing a camera and pressing a button does not in any way mean that the operator has looked at or understood what was before him.

I usually started the Portland tour by climbing up the track down which great blocks of stone from the quarries were lowered to the waiting barges below. Then, turning in the direction of Weymouth Bay, I would look down into the Admiralty dockyard with all its fascinating activities. It may have been here in the solitude I always desire that I began memorising what I saw before me. When I became an artist for the Admiralty this ability was a necessity. The last commission I was given at the close of the second world war was to go to Portland dockyard and draw two German submarines, the first to surrender after the armistice.

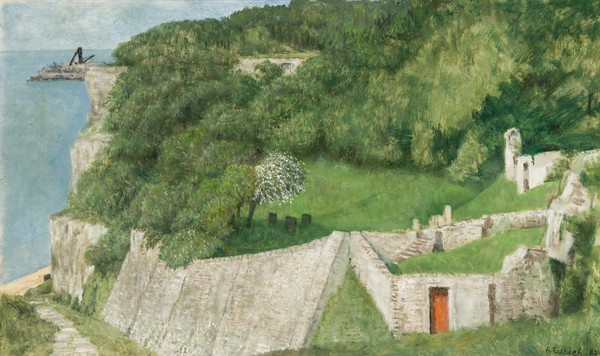

Old Cemetery, Portland (1983)

The mysterious seclusion of the old cemetery at Portland remembered nearly 60 years after Richard had sketched it

From the heights above the sheds and shipping, I climbed up again to where the prison was, and round to Church O....? Cove, a romantic spot dominated by Bow and Arrow Castle. But here on the side of the cliffs was something unexpected and mysterious. There are hardly any trees on Portland, so to find a thick stunted huddle of trees so windswept that they appeared like one thick bush with a tunnel leading under them of curious shady quietness, and a wicket gate at the entrance suggesting a new phase in some Pilgrim's Progress was surprising. But there, half hidden in the long grass and brambles lies a tiny cemetery, headstones marking the graves of some long-forgotten seamen, facing, on that steep slope the radiant blue of Weymouth Bay and the chalk cliffs of St. Alban's Head in the hazy blue of the distance.

The dust and white stone of the island always radiates a feeling of blinding light so that all becomes monochrome, intensifying the blue of the surrounding sea. From Bow and Arrow Castle the road along the top of the island runs past the famous quarries gradually sloping down to the plateau at the Bill in which stands the lighthouse. A little to the right is the Pulpit Rock and I remember on one occasion, one of my cousins and I were perched up on it with great rollers pounding in and passing us to break on the shelves of rock behind us. One mountain of water bearing down upon us was so large that we both could have sworn that the rock rose like a boat before its majesty.

Walking back along this side of Portland, up greasy slopes, brings us back to the five hundred foot high cliffs overlooking Dead Man's Bay and the town of Portland itself. Looking over these cliffs down into the sea below are the remnants of ships' boilers and other wreckage and at one time there was a beautiful French schooner right up on the beach. But I am also reminded of a day when I had been drawing down in the bay and one of my cousins was with me. Some kind of madness seized us and we started scaling the cliffs. The first half of the climb was easy going except for the loose surface but the last rampart towered almost sheer above us. How we got up I don't know. I had my sketching bag slung about me which did not make my balance any easier. When we finally got to the top and looked back at the way we had come we both could have sworn that a voice said 'You fools!' but there was no-one in sight. From up here the Chesil vanishes away into the far distance and behind it the fleet running up to Abbotsbury with its ancient swannery, the downs lazily curving inland with the little tower on the hill in memory of Nelson's Captain Hardy. My cousin's house overlooked Portland Roads and when a southerly gale was blowing, the Atlantic rollers pounded Chesil Beach and we could hear the screech of the shingle and thunder of the breakers and sometimes one could even see a white top over the beach. Whenever I saw this I made tracks for the Chesil. In fact, it became quite a standing joke in the house that if they saw me going off loaded with a sketching box, it was unnecessary to ask where I was going. The long trudge over the loose shingle was exasperating, the sound and fury coming from the other side was the most magnificent music on earth to me, and then when the crest was surmounted, the wind almost threw me back again and the spray stung my face and took my breath away. But the sight of these tremendous seas being slowly and magnificently rolled and unfolded on to that steeply sloping mound, eighteen miles of pebbles screaming as the surf pulled them back to be flung up again with deafening clatter brought a constriction of the throat and a feeling of elation.. There is no ground swell here as the beach runs down under the sea in steep shelves so that a ship of considerable size could be thrown on to the beach. Legend has it that a schooner was once lifted right over the beach on to the calm waters the other side, but it is difficult to believe.

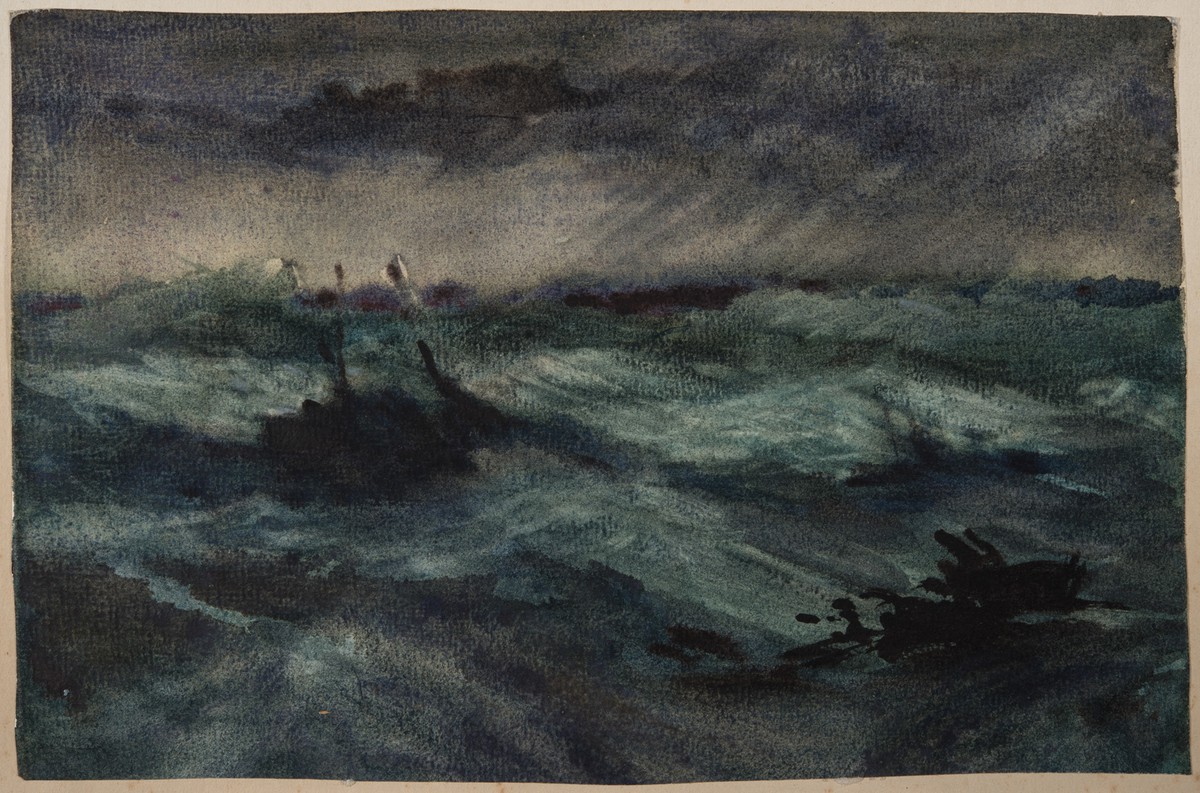

Storm (1920s)

A tempest which was probably recorded in paint back in the quiet of the house, away from the turmoil

It was on this scene of glorious dazzling fury that I proposed to spread my sketching box and paint! I had to load the box with pebbles and bury the tails of my oilskin. Unfortunately I wore spectacles and of course, these were drenched and salted up in a few seconds. They were almost blown away and I had to do my best without them. The paint only went on the panel with great difficulty and I usually used some thick vehicle like Megilpo to help the pigment to stick on. Needless to say it wasn't my idea to make a picture on these occasions. The feeling that just to watch was not enough impelled me to attempt to sort out the structure, waiting for successive waves, to observe exactly how the forms behaved when they reached certain climaxes in their headlong plunge on to the beach. An occasional gull would be blown past me to recover its balance in the comparatively calm air behind the beach and soar up on the wind to continue its vigil over the purple and green water.

On warm sunny days I came to Chesil for a different reason. Standing on the crest and looking along it towards Abbotsbury with the sun behind my back, a strange phenomenon presented itself; the heat from the pebbles usually quivered making the contour irregular, and where the bend occurred the breaking rollers assumed very strange shapes. But under certain conditions, with a deep indigo sky behind it, the glow of the beach was reflected upside down in the heat, turning upwards like a great flame high up against the sky. This subject and other paintings I made are unfortunately lost but the experience gained and the memory of these happy hours without another soul to be seen will remain with me for the rest of my life. It was here too, that I came to be quiet and read Lord Jim and Typhoon by Joseph Conrad.

The Blue Barge, Weymouth (1934)

Subject matter not noticed in his student days, but painted and sold in 1934 for a sum sufficient to get married on

I visited Weymouth many times again and I was surprised to find what I had missed in the way of good subject matter for painting. How many hundreds of times I must have emerged on to the quayside from the Brewery yard and seen across the harbour the Ship Inn and its neighbouring old buildings with a cement barge moored alongside. And yet I must have known it fifteen years before I saw it as a painting. It was my first really successful painting and I got married on the sale thereof.

It would seem that rightly or wrongly in those formative years I was not looking for 'pictures'. I was just curious and most deeply moved by the elements and desired to discover something of their secrets and record them however crudely. I was indeed shocked later during a long correspondence with Edward Wadsworth, when he wrote that the sea was not a paintable subject and could only be introduced into a design if it occupied a strip not more than one seventh part of the area of the canvas. I replied with the question 'What about Claude and Turner?' He answered 'Well, what about them.'