Tugboat (1921)

Probably painted on a visit to Liverpool but harking back to the Cartwright Hall painting of Rochester River by Bertram Priestman shown in Chapter 4

The first winter at Ilkley opened my eyes to the great beauty of landscape under weather conditions, which in the town were only the signal for putting on more clothing. I loved Bradford under snow and had attempted to paint it, but snow on the moors was a very different matter. The colour of the rocks above our house assumed a richness undreamt of, the oranges and greens and deep purple under the brilliant white with incredibly blue shadows had to be painted. I tackled two or three from my studio windows with some success but again I felt that it was more desirable to get out in the landscape. The snow did not stay long that winter but a rapid thaw brought more excitement as I woke in the morning to hear a roaring rushing sound which I gradually realised must be the beck at the end of our road which in normal weather, was a pleasant stream flowing down from the bogs on the tops of the moors over boulders and shelves of rock, under a bridge or two and through fields until it joined the Wharfe in the valley below.

I dressed quickly and went out to find a raging torrent of surging water that looked like beer rumbling madly over the black stones, which gave the name of Blackstone Beck to this stream. The golden brown in the water was caused by the peat on the moors. The small pine trees on either side of the beck also looked almost black and the deep tones of the dead red bracken still held patches of brilliant snow like white horses on a rough sea. I drew until my feet were numb with cold and then made for home again for what I considered a well-earned breakfast. I was still in charge of the central heating and got warm breaking up the large chunks of coke for the boiler. Then Father and I made our way down to the station to catch our train to Bradford. These journeys too were a delight, passing through cuttings and into tunnels, to emerge high above valleys with mills or through wooded slopes, the trees looking so sombre in their umbers and purples. The trees in Bradford itself were all bleak with soot deposit as were the buildings. But here again the melting snow had swollen the Bradford Beck with dirty water, which was such a contrast to the deep brown of the River Wharfe.

I found work at the school of art difficult with all these new experiences crowding in on me and it was a relief to be travelling home again in time to see the winter sunsets of incredible brilliance over the sombre landscape, the smoky atmosphere intensifying the blues and purples.

Tugboat (1921)

Probably painted on a visit to Liverpool but harking back to the Cartwright Hall painting of Rochester River by Bertram Priestman shown in Chapter 4

For some reason I made a visit to Liverpool to see some old relatives at Birkenhead for a day or two. I had never seen docks under winter conditions and when I arrived home I painted a sunset over the docks with a steamer churning up water all emerald green and orange. I must have used many dangerous colours on this work but to-day it still looks as fresh as when it was painted over thirty years ago. I showed this picture to the life master and my friend who was about to go up to London to the Royal College of Art. I rather had a feeling that it would be frowned upon and it certainly was! I think there was a certain snobbishness creeping into painting at this time. It was generally thought that if a layman liked a painting then it must be bad. I had let drop a word that Father had liked this sunset so it was damned accordingly. But there was also another reason: sunsets just simply weren’t done. They had been finished with long ago and now we only dealt with form, significant form. Somewhat bewildered by this new trend I began to play truant and stayed at home where I went out and drew rocks and painted waterfalls.

The second winter, after the long stay at Weymouth, produced weather to my liking. The Wharfe was swollen and I decided to take my large sketching box up to the Strid above Bolton Abbey. I had been studying the small waterfalls on the moors, trying to find a way of interpreting the different tempi involved; the jet of water falling into a deep pool from which it flowed at a different pace, then quickening again as it thrust into a narrower channel. I was always terrified of the Strid, partly due to the number of fatalities among people who made the seemingly easy jump across the rocks through which the whole of the River Wharfe flowed. But the setting too had something to do with my feelings. The river flows over stones, through pools and shallows with trees growing near the water’s edge, all serene and of pastoral beauty, and then suddenly a shelf of rock appears which persists for a few hundred yards. The river flows into one central fall but only for a few feet into a chasm containing perhaps twenty, perhaps forty feet of water, brown and sinister, little eddies and whirlpools speaking of the under cutting of the rocks all worn smooth with curious hollows made by thousands of years of water passing over them. Lower downstream the flow is even slower and more silent. Here the bodies of the unfortunate appear about a fortnight after their failure to jump the Strid. I set up my box and started painting. There were no visitors at that time of the year and yet through the incessant noise of the water I began to imagine voices and other sounds. Then a decided new sound of higher pitch crept into my overstrained hearing, becoming louder and louder, the light deteriorated and large hailstones clattered down on me, filling my box in a few moments and making work impossible, the paint no longer adhering to the panel.

When the snow came I decided to paint on the moors. I selected a spot high up as I wanted a spacious view. I took a camp stool and painted for a couple of hours, quite engrossed in the effort of recording the bleak landscape under these conditions. When I came to pack up I found I couldn’t move. My legs were quite numb and my hands blue. I felt rather alarmed as no one knew where I had gone and darkness was falling. I slowly made my stiff hands shut the box and let it slide to the ground. This upset my balance on the stool and I fell over quite stiff into the snow. I lay there gradually getting some movement into my limbs and as the circulation got going the pain was intense. I got to my feet slowly and forced my stiff legs to take a few clumsy steps. Bit by bit my pace quickened and when I was not far from home I was singing 'The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light' with gusto. I did not often go out like that again without giving some idea of where I was going and it also brought home the impossibility of really constructive work under such conditions, so I made drawings and small oil sketches and embarked on a reconstruction of them in the studio.

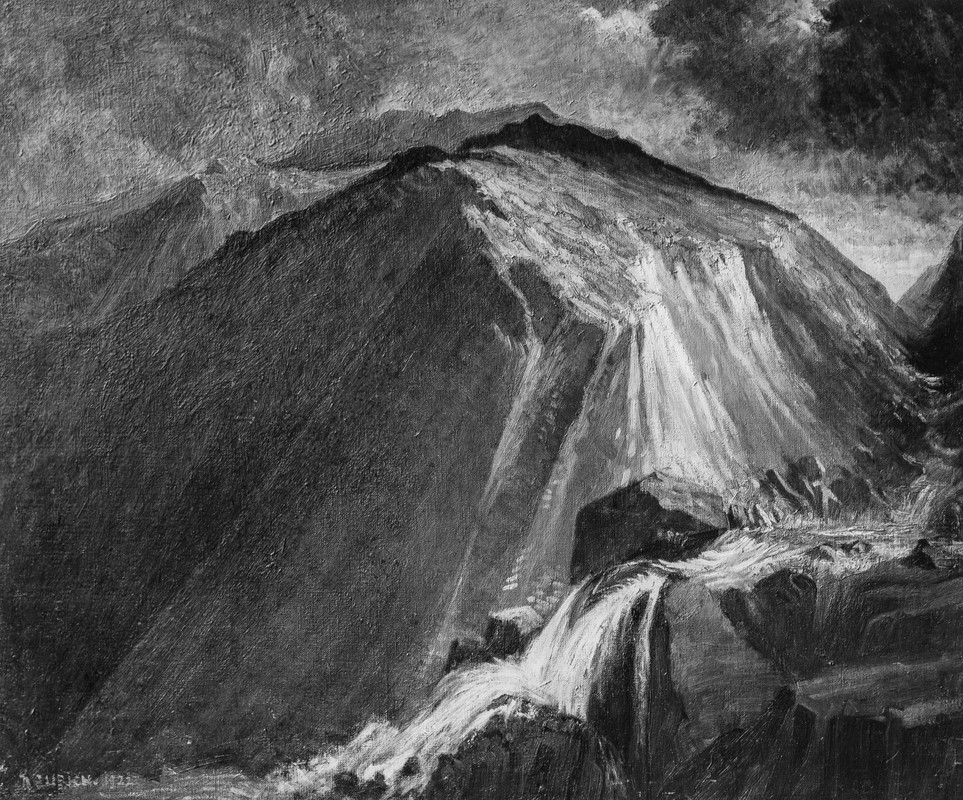

The Torrent (1922)

‘The Torrent’, a painting to be proud of

The painting that emerged which I called The Torrent was exhibited at the local Arts Club exhibition and brought me my first press notice. But the exhibition was opened by none other than the distinguished 'Father Brown' who in real life was Father John O’Connor. My Father knew him quite well but I had not met him before. He invited me to go to see him and a few pictures he possessed. Eric Gill was working at this time on some Stations of the Cross for Father O’Connor’s church in Bradford but I did not meet him there. I had lunch with the Reverend Father who sat twiddling his thumbs over his rotund paunch beaming with good humour. He expressed the wish that he could find a tailor who could make him slim and graceful. He gave me my first sherry, the flavour of which took me completely by surprise and made my eyes water. He was a man of infinite good humour and worldly in the best sense. The 'goings on' at concerts delighted him and he was never tired of telling me the story of the Theatre Royal when a Shakespearean Company were giving a matinee there. The gallery was full to capacity and more with school children, most of them paying their first visit to a theatre. They were thrilled and packed against the safety grid overlooking the well of the auditorium. One small boy who was wedged in tight felt that call of nature so natural under exciting conditions. He probably had not been instructed about lavatories and in any case, it wasn’t likely he would miss anything on the stage even if he could have got out, which was doubtful. So what could be more natural than to utilise that vast dark open space of the auditorium as a convenience? During the actual operation that followed a cheerful voice rose from the stalls to the gods; 'Wave it about a bit, sonny, wave it about a bit! Father O’Connor once asked my Father whether he would like to see High Mass celebrated. He himself was not the celebrant and so sat by Father and explained everything as the service progressed. He punctuated the story by commands such as 'stand up' 'sit down' 'kneel' and so on but also interpolated stories of a Rabelaisian variety into the narrative which reminded my Father of the kind of conversation which surgeons carry on while at work on the most complicated brain operations. This uninhibited attitude to life made it comparatively easy for Father to discuss Roman Catholic patients who required very special mental attention with the Reverend Father. Revelations of abnormalities usually unmentionable at this time he took in his stride whereas Ministers of Religion in other denominations tended to be shocked or not to understand the implications and what was being asked of them by a medical man.

After lunch he took me to his study and there displayed a life size drawing, full figure, by Eric Gill of one of this artist’s daughters. It unrolled like a Chinese painting. There was a painting by Edmund Stott of a field of cabbages. It must have been one of the first paintings I saw which had that direct simplicity of vision, nothing forced or imposed on the subject, just a scarecrow or a spade sticking up through the cabbages giving the picture a point of rest. But his treasure, to me was a tiny oil painting by Turner which I thought was probably a study for Hannibal Crossing the Alps all grey and juicy, the flavour of it remaining with me long after I could remember a single detail or object in the painting.

Father O’Connor took the trouble to write to me once or twice with a caution thrown in not to listen to those he called 'The Art Jabberwocks'. Father used to give him news of my progress and on one occasion, when he reported some minor success, Father Brown commented 'Well, what did you expect?'

But The Torrent also made one other appearance. Someone at the Art School decided that the students should bring their best work making an informal exhibition of it and invite some outside artist of repute to come and criticise them. Whether on these occasions students really want to be criticised or just given a talk and pleasant words of congratulation shared by the members of staff, I really do not know. The work was put up on the racks on one wall of the life room where some drawings on loan from John Rutherston were shown. There wasn’t room for all the work so in some cases they were one behind the other. We invited a painter to come who at that time was making quite a stir with his paintings and drawings and who had some rather strange ideas which he propounded at lectures to Art clubs. I put my Torrent picture in the show and there were quite a number of paintings by elderly ladies who came to paint from life. They were mostly drawings and studies for compositions.

It must be terrifying for an outsider to be flung into a room with a lot of students gathered round and to there and then start making interesting remarks about pictures mostly inept and boring in the extreme, which he has not seen before. There were quite a lot of us there as some evening students had brought their work and had turned up to hear what was said. We had to stand as there were only a few ‘donkeys’ in the life room and we had to wait rather a long time; in fact, knowing that the guest was given to visiting places of refreshment we began to wonder whether he would turn up. However at last, hesitant footsteps were heard coming along the corridor, the door was flung open and an enormous man was propelled into the room and stood gaping at us for a few seconds. The Principal then made an introduction which gave our friend time to adjust himself to his surroundings.

He started off by saying how he remembered that the teaching at this school had always been of a very high standard (which was not very welcome to the staff as they considered the teaching before their advent to have been particularly bad) and what an honour it was to be invited, etc., etc. Actors have found Bradford audiences very sticky or lacking in response and Bradford had been called 'the Comedian’s Grave'. Whether the sight of these gaping mouths and vacant looks gave our guest thoughts of a similar nature, I wouldn’t be surprised, but he turned to the works displayed and talking to the wall moved from picture to picture saying 'I think this one very beautiful, and the next is very beautiful too and so is this one' and he came to The Torrent at which he looked longer than most and finally remarked 'I must congratulate this student, he should go a long way' and then passed on to liking the others very much and began pulling those forward which were behind and commenting on them. Well, this was all right but it wasn’t getting us very far and we were all getting a little restive when he pulled aside a picture to reveal a drawing by a well-known artist lent by Charles Rutherston and he proceeded to say that he quite liked it but -, and it was at this point that our life master was heard to clear his throat preparatory to interrupting the flow of remarks which were becoming increasingly interesting and critical. Very promptly two or three students effectively silenced the would be interrupter and the party began to warm up as did our guest as criticism of one ‘master work’ after another laid reputations at our feet which we had without sufficient judgement thought should remain on pedestals. It was most instructive. We all showed a little animation and our friend beamed with pleasure. I was introduced to him and he shook my hand with a fist as large as a leg of mutton and then vanished; no doubt in search of well-earned refreshment.