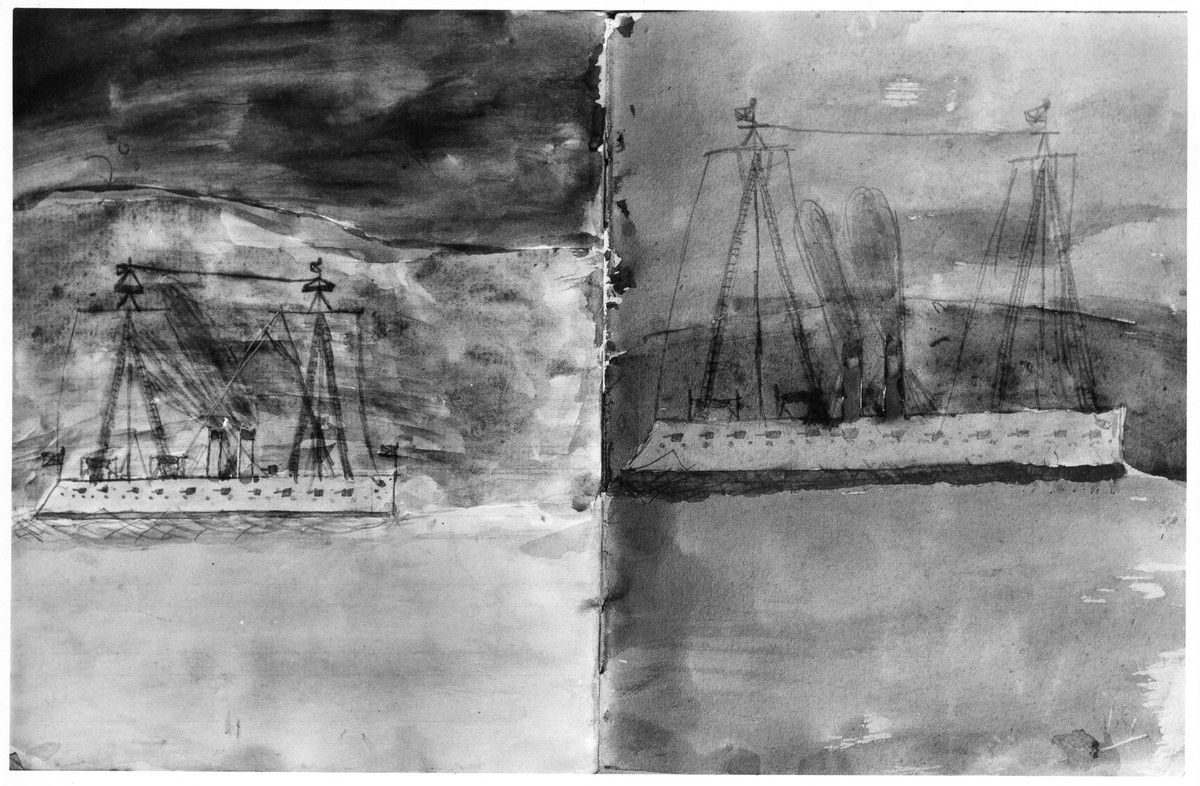

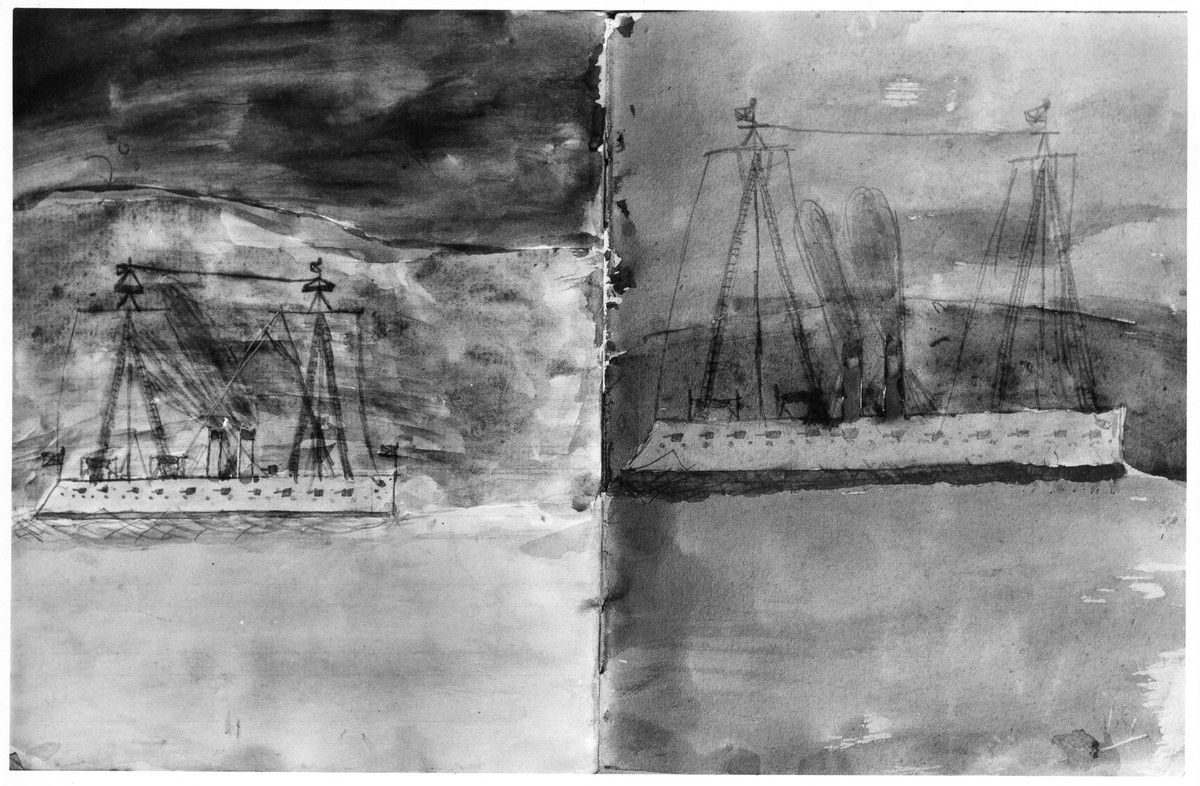

Warships (1911)

Fly-leaves from a school exercise book where the class was taught the basics of watercolour painting by Miss Rendle

At five, being of school age, I joined my elder sister at the Kindergarten. We had the full length of the park to walk through and nearly as much again. We trudged through all weathers being well equipped with galoshes, snow boots etc. I hardly ever remember going by tram during the four or five years I was there. Mother came with us sometimes and seeing her returning home from the class-room window I felt homesick and sorry for her having to walk back all that way alone. It may seem strange to relate that all I ever learned at school was taught me here. Four years at the boarding school was scholastically barren and of the two years at Bradford Grammar School, the second year only was fruitful in that I learned to like Shakespeare.

Rossfield School was well organised and up-to-date. The washbasins in the cloakrooms had a notice over them, which I soon deciphered: 'Please leave the basins clean and tidy as you would like to find them', a very good first lesson. The whole school fell into line in their own form rooms first thing and when the piano struck up with 'Toll for the Brave' played with great verve, we filed into the big kindergarten room or hall in a continuous stream. A teacher stood at the junction of the doors to see that the drill ran smoothly. Then we had prayers. The words of the hymns we sang must have been learned by ear and I remember coming back to school after an illness to find them singing Kipling’s Recessional. The words 'how all our pom pom yesterday' seemed very odd to me but we sang it with gusto.

Miss Gregson was the headmistress but Miss Rendle was the life and soul of the school and no doubt was the brains behind the management. She had tremendous enthusiasm for everything. She was a suffragette, vegetarian and a terrific talker which made me want to keep at a reasonable distance. It was not always easy, as she was always very much in earnest, leaning forward with that slight frown on her forehead, which, together with a windblown complexion gave her a somewhat masculine appearance. But she had a beaming smile that endeared her to the most timid. She bounded about brimful of energy in a long tweed skirt with a leather belt and a loose blouse and shapeless woolly jacket. She had a peculiar scent about her that I have never been able to name. I have sometimes wondered whether it was some kind of snuff! Her hair was pulled back into a bun behind her head with some untamed strands sometimes coming loose.

Miss Gregson looked the dragon she was. Full busted, straight as a soldier, well corseted, with a high collar stiffened by whalebone and a barbaric brooch of a very spiky kind on her front. No little head ever sobbed its heart out on that bosom. Her dress was black or dark grey, her hair white and immaculate in its stiff wave and bun on top. She was unbending in everything she did and talked in a harsh dry unmusical voice. She taught mathematics and punctuated her speech with a pair of gold rimmed pince-nez which, when not in use, kept company with the spiky brooch on her bosom.

Miss Rendle taught practically everything. She taught us how to fold paper covers for books, how to make a paper box with a lid which had to fit and so had to be a small fraction of an inch larger. The word 'accurate' was constantly on her lips. From paper we went to cardboard and from cardboard to 'Sloyd' and here another old lady comes in. Her name was Miss Willis. She was bent nearly double with a hump back. She had a sister, who was likewise afflicted, as was her father, who must have been as old as Methuselah. But she was one of the most charming old ladies I have ever met. A humorous gleam never seemed to leave her eyes. She had to screw her head round to look at me, as she couldn’t raise her head on her neck. She taught me how to use the Swedish knife both on wood and cardboard and I have always considered this the foundation of all I know about tools and wood.

Miss Rendle had a genius for organising children’s games. 'Now boys and girls, we are going to be trees' etc. and so we stood, arms outstretched, swaying slightly and fluttering our fingers, the leaves.

At first I came out of school earlier than my sister Margaret. So the arrangement was that I called at Miss Gregson’s house, five minutes walk away, and go into the kitchen. There were two maids; one was Emma Topham. She had been our cook when I was born and she doted on me. She wore a blue and white striped cotton dress with stiff starched cuffs and high collar like a man. She was very wrinkled and had a leathery voice, which sounded as though it was going to jump up an octave. She gave me biscuits and sweets. The other maid was younger and always jolly. But the memorable thing was the postcard album. It was marvellous. Photos of all the Edwardian music hall beauties, royalty and Blackpool, not to mention the kittens in baskets and silver horseshoes with forgetmenots. To this day I can’t throw a picture postcard away but my collection is very dull compared with theirs. I never got tired of it. Then Margaret came, and off we went home.

We always met the same people in the park. There were two spinster sisters, one stout, and the other slim. They dressed in purple and had hats perched high on top of their heads, the flowers in their hats quivering at every step they took. Their tightly corseted dresses were covered with a maze of black braid or binding and they always carried neatly rolled umbrellas with long ornamental handles. They always smiled at us and made jokes about our not wearing hats. There was always the old unshaven man with his hands and chin on his walking stick sitting near the park gates. He watched us approach with his red-rimmed eyes. We tried not to make a slightly circular progress in our walk but we knew he would hiss out something quite incomprehensible at us as we passed. I never knew whether it was a form of humour or otherwise.

In the summer we kept to the paths under the trees and played games hiding behind them and jumping from stone to stone where these formed a border to a bed of flowering shrubs. In the autumn we shuffled through the drifts of fallen leaves, kicking them up in a flurry like a ship plunging through rough water. In the winter there was snow, so we took our sledges. The gathering of these sledges at school was a wonderful sight; large sledges, small sledges, home made sledges, big toboggans, high ones and low ones. Some were gaily painted, others just plain wood and some were made of steel tubing and had some sort of steering gear. Margaret’s sledge was a high one with flat runners and did not keep on its course too well. Mine was a low one with round runners and was most suitable on an ice track. In the thick snow it was almost like a snowplough. It simply collected it up and piled it onto my legs with the result that I got very wet. One day on our arrival home Mother seemed to think I was even more saturated with icy water than usual and on further investigation discovered my pockets were filled with snowballs

There was a scheme at school to encourage us at gardening. On the north side of the grounds small plots about six feet square were allotted to us. But waiting for seeds to come up was too slow for many of the boys who soon got tired of horticulture and, having plenty of energy to work off, began an attempt to dig a tunnel under the school wall. One said he was going to Australia. Some of us spent much time constructing paths and we toyed with the idea of making a pond or a fountain. Miss Rendle never grew angry and listened to our ideas patiently and reasonably and to such questions as to whether sowing caraway seeds would produce seed cakes, she responded with good humour. But to see her in her element was when she took us for Nature Walks. I can’t remember how often these took place. They were educational and not all 'nature'. She took us to a pottery where they made earthenware baking bowls and great jugs and mugs. We all came away with a mug each with our names on them for the price of one penny. And there was the rope and string factory. The smell of this place had something of a hayfield and remains fresh with me to this day.

But the real Nature Walks began fairly sedately with our botanising tins over our shoulders and Miss Rendle now with a man’s fishing hat fixed to her bun with two hatpins and at her leather belt a sheath with a trowel stuck in it. We usually went to some outlying part of Bradford or to the moors. We listened to discourses on buttercups and celandine but being out-of-doors was very different to the schoolroom and we soon got up to mischief. There were streams to play pranks in, caves to hide in and all the little things that only small children can think of, we thought of. Then of course, there was the picnic tea. We had all been instructed to bring fourpence and this was spent on penny teacakes and ginger beer or lemonade. Miss Rendle had a whistle on a cord and she blew mighty blasts from time to time to gather the flock together and see that none of the sheep were missing. The ginger beer and lemonade were in glass bottles with a marble secured under pressure in the neck. Releasing this was always a bit of a performance and when finally it had dropped down into its socket in the neck, as often as not the contents of the bottle shot into your face. If you were lucky enough to avoid that pitfall, there was the danger that the bottle might become firmly stuck in your mouth or that your tongue might be sucked into the neck. By the time the walk was over we must have looked as pretty a set of urchins as ever came out of Bradford.

There was one thing, though, that haunted me through all my schooldays. This was arithmetic. I dreaded the time when I grew older and would have to buy a railway ticket for myself. When Father booked tickets there was always so much counting of change and writing down in a ledger every penny he had spent. I was quite sure I could never do it. I never attempt to count change even to this day, always relying on the accuracy of the shop keeper or bus conductor. Simple addition still eludes me and I always fall back on the method of counting, domino fashion. It was not long before I was ‘kept in’ for arithmetic and had to go into the upper forms when my lot were playing outside and be under the cold eye of Miss Gregson. But it was no use. Mother tried to help me. She even got a coach in to give me extra arithmetic. I sometimes wonder whether Miss Rendle understood and saw visions of something more important than maths. Many years later (she had a habit of bobbing up in one’s life at odd moments) she was talking to me about my future when it was definitely understood I was going to be a painter. She looked at me with earnestness and a certain perplexity, having had a sample of my rather obscure talk, the saliva gathered round one of her gold fillings and then she said 'But you are not going to be one of those cubicle painters, are you?'

We drew on blackboards quite a lot at school and if we drew something outstanding it was not immediately wiped off but allowed to stay for a day or two. I frequently had this honour though I had rivals. These were the usual clever girls who could draw fairies. But more serious was another who could draw ships. He was Edgar Beldon, the twin brother of Eileen Beldon the actress. I heard of him from time to time later and it seemed that our rivalry continued. Unfortunately he lost his life in the Second World War, being found dead in a boat which had capsized.

Warships (1911)

Fly-leaves from a school exercise book where the class was taught the basics of watercolour painting by Miss Rendle

Next we learned something of the craft of watercolour painting. The modern use of powder colours in schools had not been started. We had to wash the paper over with a brush and then give it a wash of yellow in the middle and, while still damp, another of red and another of blue down to the bottom of the paper. We then turned it upside down and there was a sunset! Then we could put in a landscape with palm trees or a blue sea if we liked.

We modelled in clay. It was a rich terra-cotta colour and the wet clay bins smelt earthy. I loved to stir water into it when the clay was too stiff. When something better than the usual unrecognisable lump of tortured dough turned up, it was displayed on a window-sill until it broke up of its own accord.

We illustrated our homework. My books, whether scripture, history, geography or even arithmetic, were more illustration than literature. I still have some of them. Mother’s handwriting is constantly in evidence. 'Please impress on Richard what he has to do for his homework. He has drawn David and Goliath.' Or the teacher’s red ink savagely ruled across a drawing of a Christmas tree with the comment 'This has nothing to do with the story of Moses' and the news that Solomon had a menagerie brought forth a drawing of monkeys in a cage. The teacher’s remarks were 'You might have spent more time on the animals and less on the cage'. The story of Eli falling down dead off his chair for some reason inspired me to draw a chair. This brought forth the teacher’s remark 'The chair is not the most interesting part of the story'.

We had musical games and community singing. For the latter an expert was imported in the shape of a gentleman with a huge moustache, Mister Kafaire. His name was probably Kaefer. He was Belgian and it was rumoured that he was a pupil of the great Ysaye but how he found his way to a kindergarten in Bradford isn’t easy to imagine. He brought his violin with him and, after going through a folksong in the sol-fa system, he would take his violin out and make a show of tuning it. He would point his bow at some unfortunate child and make some pleasantry to the effect that he could pick him up on it like a toasting fork and gobble him up. But I never remember him playing the fiddle. He may have joined in when we sang but we couldn’t hear him. It was said that one hostess, more daring than others, had invited him to play at a musical evening and had to reprove him for tuning his violin while some lady was singing. For some reason the folksong Cock-a-doodle-doo - such a curious song for children - always reminds me of him. Perhaps it is the 'fiddling stick' but I can remember him capering about rather like an old time dancing master while we were singing the song. But there was one song that terrified me. That was The Raggle-taggle Gypsies. The harshness and bleakness of the narrative was so contrary to everything I held dear and the ruthless tune seemed to hammer it home. The images of haunted roads and copses and the lady in a cold open field appeared in my dreams. But I always liked melancholy folksongs the best and still do. Jolly songs, drinking songs and general rollicking depress me profoundly. So frequently a composer winds up a song-cycle of a wistful, contemplative nature with some jolly nonsense which completely obliterates the atmosphere that had been created.

The number of crafts we were taught made me wish to employ them on something more interesting than paper mats, pen trays and other ‘useful’ articles and so was born a passion for model theatres. I made quite a number of them. The actual play to be performed was a minor consideration and I can hardly remember giving a performance. Certainly there was never any talking. This is a gift I do not possess and to have to learn a speaking part is quite beyond me. Arithmetic is certainly a closed book to me, languages ring no bell, but learning a poem or speech or even music by heart is torture. Memory seems to work entirely visually with me and in any case I have always been far too shy for anything in the nature of a public performance.

We had an annual pageant or something like it at school. In my first year I played the part of a lamb being dressed in white woollies with a white cap. The semblance of a lamb was given by some ears (more like a donkey), being sewn on to the cap. I haven’t the faintest idea in what context the lambs appeared (there were several of us) but we had only to crawl on hands and knees in front of the footlights and back. I had to be pushed on and kept on by a girl I secretly admired who was also a lamb but much more willing. The year after this debut I was promoted to being one of six sailors in the Spanish Armada. This was, of course, a non-speaking part and entirely decorative. I believe I was subsequently one of Robin Hood’s merry men dressed in green. Again this was just another part to give the effect of a crowded stage and no one could have called me ‘merry’.

I suppose the proscenium and scenery, lighting and curtains and backcloths were what fascinated me about the theatre. Trap doors and any ingenious device interested me, whether it was eventually used or not. Some of the more thoughtful boys and girls became friends of mine through these interests but they were no doubt disconcerted when they found that once the curtain was rung up and the stage was set I wasn’t with them. But I did once go so far as to construct a kind of ballet with toy soldiers, of which I had a fine collection. I fixed a row of highlanders to a wooden bar that was operated from the wings, sliding them in and out again, while another bar had hussars mounted on horses. Cotton thread was tied round the neck of some hero who danced a solo in the centre while a horse-drawn gun team rattled across backstage. Further than that I never got with a performance until years later my wife and I gave a show with a glove puppet theatre of our own making. It is certainly a mercy to me that a painter does not have to appear before his public and contrary to the generally accepted idea that an artist enjoys ‘showing off’, most painters prefer to be as far away as possible from any gallery showing their work.