At Germany (1912)

Richard’s diary of the visit to relations in Germany before the War show the military marches in the streets

In 1912 we moved house again. Father had heard that trams or trolley buses were going to run up our road. It was quite noisy enough already so he decided we must move. So again we moved only a few minutes walk away into a private road with gates at the bottom, also leading into Manningham Lane and two roads nearer the town.

When the transaction had been completed we all wanted to know what the new home was like. Well to begin with it hadn't any gas. (For a moment we were amazed and then Father, having had his little surprise, explained that it was lit by electricity.) This was really exciting but for a moment all was eclipsed by a proposed visit to Germany after which we would come back to the new house.

Margaret and I went with Mother and Father. Our destination was a little market town in Saxony called Zittau, very near the border of what was then known as Bohemia. My paternal Grandmother, known as Grossmutter, was living there with an unmarried sister in a first floor flat with a balcony overlooking a street. A vine grew up the house and all round the balcony. My aunt who had married a German manufacturer also lived here in a wonderful house he had built in beautiful surroundings.

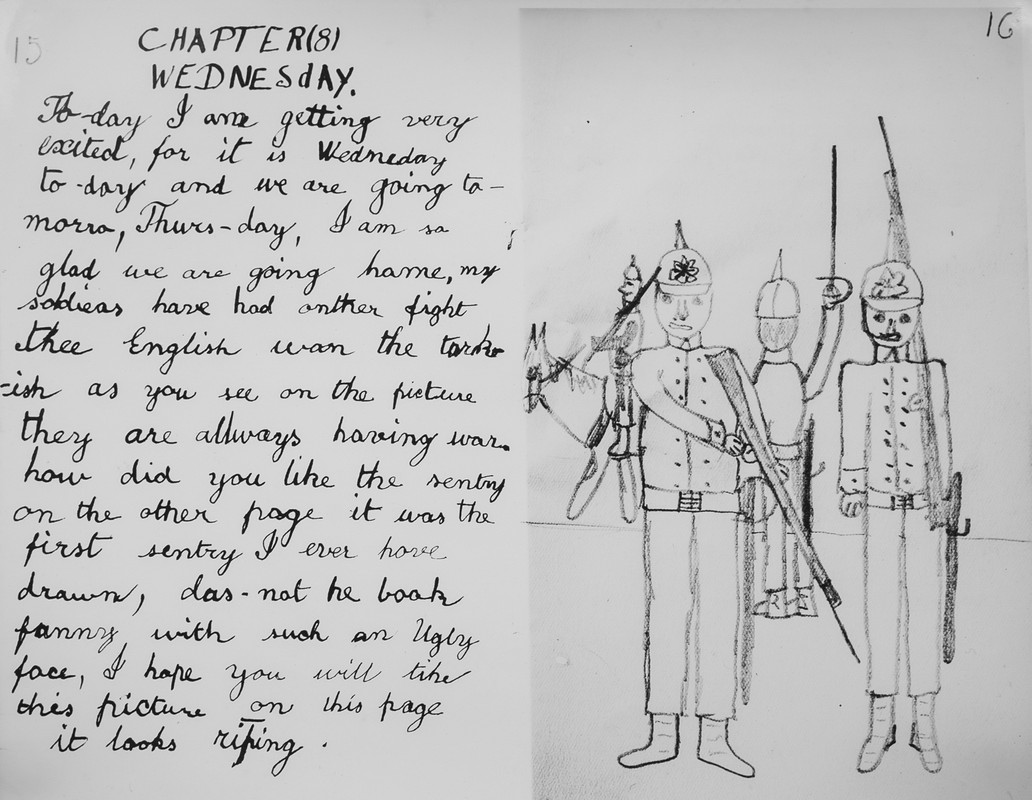

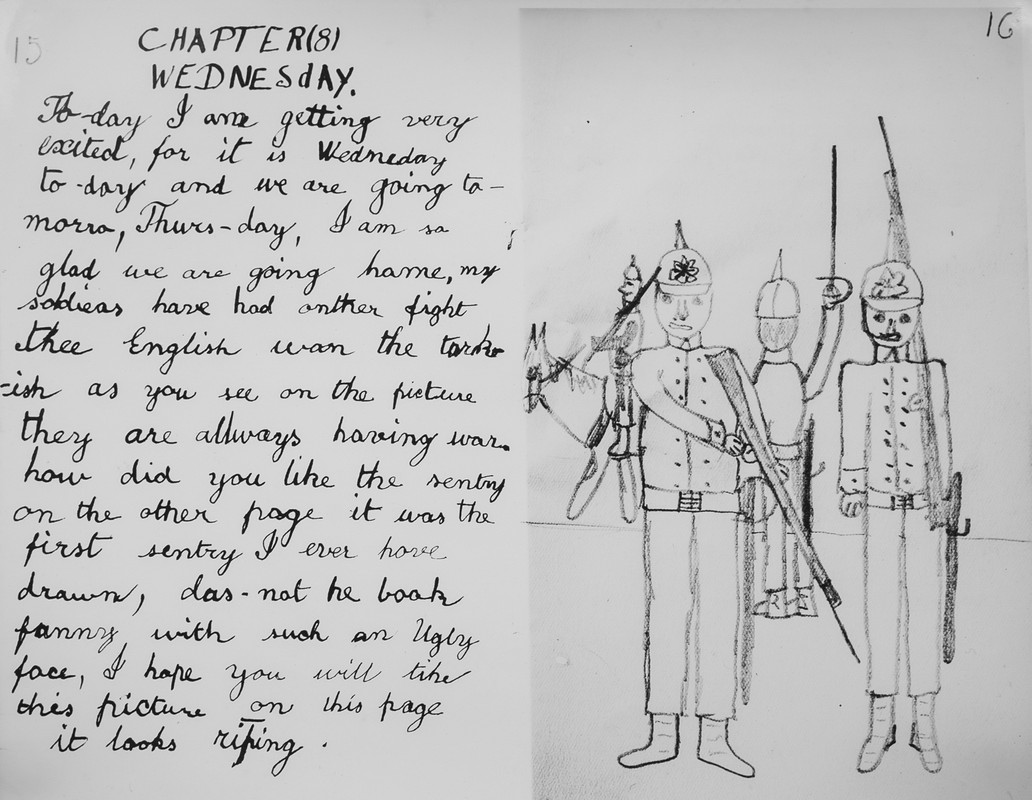

I still have an unfinished diary of this holiday, fully illustrated. Both the writing and the style are very undeveloped, as too are the illustrations for a boy of nine years old. But there are some entertaining drawings of German soldiers in their helmets with spikes on them. Indeed my memories of that time are chiefly of unending marching of soldiers with military bands.

At Germany (1912)

Richard’s diary of the visit to relations in Germany before the War show the military marches in the streets

One morning just as we were about to dress, the sound of a military band was heard coming down the street. Mother and Father were in lodgings on the opposite side of the road. They were up and at their positions to see the procession. They looked across at our flat to see if we were watching too and to their surprise, there was Grossmutter and Margaret but no Richard. What could have become of him? And then suddenly a figure stark naked appeared on the balcony! Grossmutter was horrified at this! She was terribly prim and hustled me back into my bedroom in tears of vexation.

The town had a peculiar smell pervading it. Father said it was burning peat but there were other smells of suffocating intensity that nauseated me, notably in the butcher's and sausage shops. I could not understand how Grossmutter could go into them at all and I remained outside. But the toyshops were wonderful. I have never seen anything like them. They were full of the most diverse toys: from sheets of cardboard for cutting out models of houses and soldiers, forts, trees and ships, to the most elaborate scale models of fire-engines, motor-cars, trains and dolls of any description. The market place had houses like those in Durer's pictures, and little milk carts and peasants carts were drawn by dogs.

There was a beautiful park called the Weinan, which was very popular. Margaret and I were walking alone there when we wanted to know the time. Margaret in her very best German asked a dandified young man. He had evidently heard us talking English and replied in an extraordinary complicated Anglo-German the exact time. Margaret, always conversational and realising no doubt that he wished to air his English gave him a glowing account of the recent coronation of George V and all he could interpolate whenever there was a pause was 'It may be'.

My uncle was quite an important person in the town. Having lived in England he tried to introduce some of the things he admired into Germany; among these was cricket. He supplied some schools with balls and other equipment together with a book of the rules. The teams were selected and all was correctly set up and a schoolmaster was put in charge. He held the book in one hand and directed the game with the other, reading out directions as to who did what, trying to get the whole game working in military fashion. They could not grasp the character of the game at all, individual initiative being quite outside their understanding and so any attempt to continue was abandoned.

Mother and Father left for England before we did to superintend the removal to the new house. Grossmutter accompanied us home shortly afterwards. We crossed the North Sea by night in terrible weather. This is the only time I have ever been seasick.

Mornington Villas, Bradford, 1912, with Richard's sister Guendolen and brother Hugh standing outside.

The new home was semi-detached and had a front garden with a bit of grass, a rockery and some laburnum trees. There was a drive running to the back of the house where there was a muddy patch of ground that might grow grass. The wall along the drive was only a few feet high but after a few yards it rose another foot or two and so it progressed until it met the far boundary wall, which may gave been eight feet high. The tops of the walls were quite flat and about eighteen inches wide. We soon found how pleasant it was to run along and look into our neighbours’ gardens which all seemed on different levels.

Our neighbour over the back wall was a Mrs. Rawcliffe who unfortunately had some quite large greenhouses in her ground, and our games of cricket played with a tennis ball were a constant source of anxiety to her, as well they might be. She disliked us cordially and didn't hesitate to show it. We certainly made plenty of use of these walls and the neighbours were most tolerant when we trespassed on their domains. We had a lot of packing cases that we used to build houses with. They were quite ambitious having two floors sometimes. We had meals in them but Mother would not let us sleep in them as they were not weather proof.

The inside of number eight Mornington Villas was large and there were some back stairs as well as the usual central ones. This was a great improvement in our eyes; it made the game of hide-and-seek so much more exciting. And there were large cellars too with a boiler for central heating and immense attics. At one time I slept in one of these attics and it had a view across the valley. The foreground of housetops led quite easily into the sudden forest of chimney pots, behind which rose their giant brother the mill chimney stacks. These in their turn appeared quite naturally to be part of the face of rock and quarries with their cranes behind. Then the terrace upon terrace of stone houses grew up out of the rock to the skyline. Lying in bed at night I watched this scene as the lights gradually showed up. The progress of the lamplighter spread a network of streets more or less invisible in the daytime. Then a larger area of light slowly threading its way from star to star proclaimed a tramcar climbing steeply up, sometimes disappearing behind a larger building and then appearing again and stopping to pick up passengers. As complete darkness fell it was like the Milky Way and so I continued to watch it until I fell asleep.

I frequently walked in my sleep and would wake up and find myself staring out of the window at a scene lit by moonlight, not knowing where I was. It was a frightening experience. I waited until my bearings began to trickle through to my fuddled mind and then started groping for objects known to me. Here evidently, was the mantelpiece. I held on to it for a time trying to recollect in which direction the bed lay but I could not leave go of anything and walk blind to where I calculated the bed should be. Here was a chair and here a bookcase and so round the room until I reached the large box-bed with the brass knobs. It was very high to get into and there was the fear that I might not get my direction right and fall headlong over the other side. Sometimes I had to cry for help and Mother, who was a lighter sleeper than Father, would come to my aid. The relief at being back in a warm bed again with comforting words and the bedclothes being tucked in was like a happy ending after a perilous journey.

Having a larger house to run began to bring out Mother's passion for organising her children’s activities. We all made our own beds and had other duties to perform. My task was to clean all the boots (we didn't wear shoes.) My sisters all wore boys’ boots and Mother had boots that laced up rather high so as to give support to her bad legs.

I enjoyed this activity as boots always had a strong individuality. Whenever I was taken to get a new pair fitted my choice rested entirely on the shape of the toecap. These varied in proportion so much and an ungenerous toecap offended my sensibilities. The band dividing it to form the rest of the boot was all-important; some had a pattern with a punched hole at intervals, others had two smaller holes alternating with the larger ones. Father’s boots were particularly good to polish. They were not muddy like ours so that the heels could be given special attention, the leather being in good condition. The uppers made a pleasant sound under the brush and I took good care not to get the laces blackened. Mother’s were soft and creased; these creases easily developed into cracks which distressed me. I performed this work on an old stone sink in one of the cellars and as each pair was finished I stood them in a row till the family was complete. Then I would crook my arm and pile them all into it and carry them upstairs placing them outside their owner’s bedroom doors.

The kitchen was a hive of activity. We usually had two maids but even so we were all encouraged to do our part here as well. Washing day was terrific. Father wore starched collars and cuffs, and quantities of petticoats, shirts, sheets and blankets were carried about in clothes baskets and festooned all over the backyard, on clothes airers hanging from the kitchen ceiling and on clothes horses before the kitchen fire. The thumping of smoothing irons was heard continually and when the more complicated ironing of shirts and blouses had been done I was frequently called in to do the handkerchiefs. These would sometimes run to over a hundred in number and the growing pile of neatly folded linen gave me a feeling of something accomplished.

In one of our cellars occupying the length of one dark wall was an enormous contraption which looked like a cross between a torturer's rack and a quarrying machine. It must have been quite twelve feet long, of gigantic frame in the middle of which was a winch with large cogwheels. This enabled a top chassis with chains to slide backwards and forwards on rollers, it being weighted down by a ton or two of millstone grit stones. It was a mangle, and generations of patient maidservants and washerwomen had struggled with the monster underground. What happened to the monster after I left the home I never knew. It may be there still or in some museum.

Mother wished to do away with these Victorian monsters and introduce labour-saving gadgets for her domestics. The latest mangles were purchased with all their accessories and were installed in the wash kitchen. Hosepipe curled about the floor and tripped you up from time to time in the two or three inches of water swirling about the floor. I don’t think Mrs. Sheridan liked all these improvements; she preferred the corrugated washboard and peggy tub. I don’t think electric irons were introduced as so many had to be used at the same time. Electric washing machines came much later. But other improvements were on their way: hay-box cooking, paper-bag cookery and other processes, which puzzled the maids considerably.

Then there was the knife cleaner. In the days before stainless steel, knives had to be cleaned with potato or some patent stuff. One day Mother introduced another machine with a handle. It had a wooden case, from the general shape of which one deduced that there was some sort of wheel inside it, operated by the central handle. Round the circumference of the outside shell were a number of slots into which the knives were thrust, the handle having to be in a given position. Then when all was set, the handle was turned and strange noises were heard. I believe some chemical was inserted in an aperture with a large cork in it. One thing you most definitely had NOT to do was to turn the handle the wrong way. I once did this by mistake and the effect was instantaneous. There was a terrific clonk and the handles of all the knives gave a frenzied jerk and stood to attention. I drew one out slowly and found the blade twisted and battered out of all recognition.

Then there was the marmalade orange slicer. It had to be fixed to a very strong table with cramps. A sort of guillotine knife had to be plunged backwards and forwards by a pair of willing hands. Another pair cut oranges into quarters and thrust them into a funnel behind the slicer and a third pair rammed them against the slicer from behind with a wooden ram, the slices of orange falling into a large baking bowl on the floor. Sometimes the machine came adrift because of excessive energy on the part of the slicer and got shot off the table by the weight of the rammer. All four participants in this little domestic time saver had very sticky hands, the table would be covered with juice and then the machine had to be taken to pieces and washed.

All these labour-saving devices were cumbersome objects that took up a lot of room, most of all the vacuum cleaner.

This was a great chest-like object on castors. It too had a handle, this time attached to a wheel like the old fashioned mangle. Yards of flexible tubing about two inches thick was attached to a nozzle at the bottom of the chest, which suggested the sort of apparatus used for conveying air to a submerged diver. Various extensions could be fixed to the tubing, which had a habit of coming adrift. One pair of hands turned the wheel while another pair scuffled about with the extensions; the tubing writhed about the floor like a wounded snake while the fluff from under the beds was being enticed into the chest. Suddenly the snake would wriggle itself free and the chest would gyrate on its castors making the main wheel lose control and a powerful jet of dust, fluff, bits of paper, hairpins, marbles and other debris and lost property would be backfired across the floor.

There was also a steam cooker, which required two able-bodied persons to lift it, and the preparations for use were extensive. It was likely to give off jets of steam and seemed about to explode at any moment. The maids gave it a wide berth and much preferred the old pots and pans.

We baked all our own bread and I loved baking day. Kneading the great mass of flour in the baking bowl was beyond my strength but I enjoyed flinging gobbets of dough into waiting baking tins and then watching it rise before the fire prior to their being pushed into the oven. I was allowed to make pastry and small apple pies which always appeared rather more grey in colour than those made by the maids or Mother.

When I was a little older, one of my domestic duties was to attend to the stove, an enormous thing about six feet high, which served the central heating. Mother would get in a ton of coke, which was in gigantic pieces. These I had to break up with a coal hammer and feed the stove, which had a big appetite. The clearing out of the great crusts of white-hot clinker was a heavy job and sometimes I was almost overcome with the fumes. I spent a great deal of time in the cellars as one of them served me as a kind of workshop.

I think it was on my twelfth birthday that I was given a carpenter's bench with cupboards in it for tools. This was my pride and joy. The large front cellar, which contained the monstrous mangle, was the old wine cellar and had a stone slab of prodigious size in the centre on which at one corner rested an earthenware filter. Father was very particular about the water we drank being put through this. The rest of the slab was occupied by dozens and dozens of bottles and jars containing chemicals, liquids, specimens and all manner of strange things including a viper or two that Father had killed and preserved in spirit. This cellar was very dark having no proper window. I don't think we were ever warned by Father or Mother not to touch or meddle with any of his things though the consulting room was of course understood to be out of bounds, a sort of Holy of Holies.

We always had much to occupy ourselves with and so one day, when my two younger sisters came to me in a state of excitement I realised that a discovery of importance had been made. In awe-struck voices they informed me that there was a baby in the cellar! I was incredulous. 'Yes, it's in a bottle' they said. So we all went most quietly down the stairs into the morgue and looked. It was in a wide-mouthed bottle fitted with a glass stopper, sealed up. The bottle was only about nine inches high, so the strange quiet little form in spirit can only have been about five or six inches long. In the dim light we examined it intently in a silence which became almost visible. Although we were gazing at just the bottle on the slab, I became somehow aware not only of our immediate surroundings but of the whole weight of the house above us. Of Father actively engaged in his laboratory (which was now in the home) his heavily furnished consulting room, the kitchen where the maids were working, of the back stairs running from the kitchen up into the attics, the huge linen cupboard on the top of the landing and the pigeons nesting in the eaves. The tiny baby seemed perfectly formed as far as we could see. We quickly moved it back among the forest of bottles and stole upstairs with our limited thoughts and unsatisfied curiosity. I donıt think any of us mentioned our discovery.

Sometimes, when I was up early, I would take up a morning cup of tea to Mother and Father. On one such morning I went into their bedroom. Mother reclined on her bed. Patiently, with deft fingers, she was rolling up bandages, which were flung over the foot of the bed. These were for her bad legs. Father was in his night-shirt at the wash-stand, shaving. I looked out of the window for a moment or two while Mother questioned me about my household chores, as she always wished to be in touch with what was going on. Then I turned and looked at the dressing table, which was generally somewhat disorderly and saw on it a sort of large glass preserving jar with sealed glass lid. The jar contained a strange white mass of tissue floating in spirit. I stared at it and evidently Father noticed my curiosity as he asked 'Well, what do you make of it?' It appeared to be a section of some animal form but the distortion caused by the spirit made it difficult to identify. Father scraped away at his chin. Then, without washing the stray lather off his face, came over to me and turned the jar round as though he was showing me something very precious in which he took great pride. 'It is the throat of a woman' he explained. I kept silent and gazed at it not knowing quite what my reactions ought to be. Then I noticed that there was a great gash across the tissue opening outwards slightly. 'That is a cut made by a razor' he went on. 'Now you can tell by the direction of the cut and the way it started from here and left off there that it was not self-inflicted.' and so he demonstrated conclusively what a layman might have taken for suicide to be murder. Father used this specimen in his lectures on forensic medicine to students of Leeds University. I turned to go out and saw Mother with her head slightly on one side, her lips pursed, patiently winding her bandages.

One very wet and windy night after I had gone to bed, I lay awake listening to the sounds inside and outside the house. Father was playing the piano. He played very well and, after we had gone to bed we left our bedroom doors open and occasionally shouted out requests for certain items: Beethoven's Turkish March from the 'Ruins of Athens' was a great favourite. Suddenly there was a terrific jerk on the front door pull, the sound jangling away in the kitchen. One of the maids went to answer the door, which flew open with the wind. There were exclamations and apologies and the sound of wet clothes being shaken out. Father stopped playing and came out into the hall and so did Mother. I could hear some astonished exclamations and evidently something heavy or awkward to carry was being edged in through the front door, which was very narrow. Then with hushed voices the object was being carried upstairs to Father’s laboratory which was the room next to mine. I was somewhat apprehensive as to what was going on but then heard two female voices bidding Father goodnight in cheerful, amused tones. Next morning I asked Mother what it was all about. She said that two nurses from a nursing home just round the corner had between them carried a basin containing a growth weighing nearly a stone to our door. It had been removed from a woman patient who, I learned later, made a complete recovery. Whether the specimen, after Father had examined it, took its place among the bottles in the morgue downstairs I don’t know.

As we lived in a private road there was very little traffic. I suppose only cars and vans that had business with the residents were really allowed to use it. The people who passed up and down were usually known to us. So it was decidedly unusual that very late one night or early in the morning when I was lying awake, I heard the sound of loud voices echoing in the stillness. They gradually came near and it became apparent that two men were having some difficulty in getting home on their most unwilling legs. They must have come some way as there were no public houses in the vicinity and closing time must have been hours ago. One of the men was having more difficulty in his progress than the other who was issuing words of encouragement as he acted as prop and stay. There would be the sound of heavy boots sliding in the road and a few curses and complaints as I gather they had both landed in a heap. A struggle ensued to get themselves on an even keel and then the slow business of getting under way with one propeller more or less out of action, was too much for my curiosity. So I got out of bed and went to the window and in the faint light discerned a shadow moving unsteadily in the road. The disabled propeller suddenly sprang to life, which threw out the steady support of its twin. The sliding and scraping of boots and the sprawling shadow that spread-eagled itself in the road was irresistibly comic. Again a few curses from the parties and then both sat up and looked about them. A clear rich voice raised itself: 'Dr. Eurich lives somewhere here; examines blood, tha knows'. The shadow then painfully raised itself and half slid, half stumbled on down the road.

Father always welcomed us when we visited him in his laboratory and answered any questions about what he was doing or about any apparatus with pleasure. When he moved the lot to our home we often went in to watch him working. The fine craftsmanship involved in making sections of minute delicacy to be transferred to slides, and examined under the powerful microscope, was a pleasure to watch. The freezing machine and centrifuge, and the special burner for melting glass tubing and drawing the molten glass out into a thread gave us plenty of entertainment, particularly as he allowed us to dabble in the process.

He had incubators in which he developed cultures of Anthrax, spending fifteen years working on samples of wool from all parts of the world. He hoped to be able to eliminate the infection and at the same time tried to find a means of disinfecting wool already imbued with the deadly germ, which caused such a high death rate among wool sorters.

While all this activity was going on, which was only a sideline to his growing consulting practice, it was necessary to get the workers in the Bradford mills to recognise this terrible disease in its earliest stages. A small spot on the hand, face or neck might in a few days become incurable. So Father made some paintings in watercolour of those parts of the anatomy with the early stages of the disease clearly shown. These were reproduced and hung up in the mills, with the desired effect. Later on when he was lecturing or demonstrating some point about Anthrax, he asked me to prepare some watercolour drawings on which he would superimpose the pimples and eruptions. These were my first commissions and though they could not be considered works of art, I was very proud to have taken a hand in something so useful.