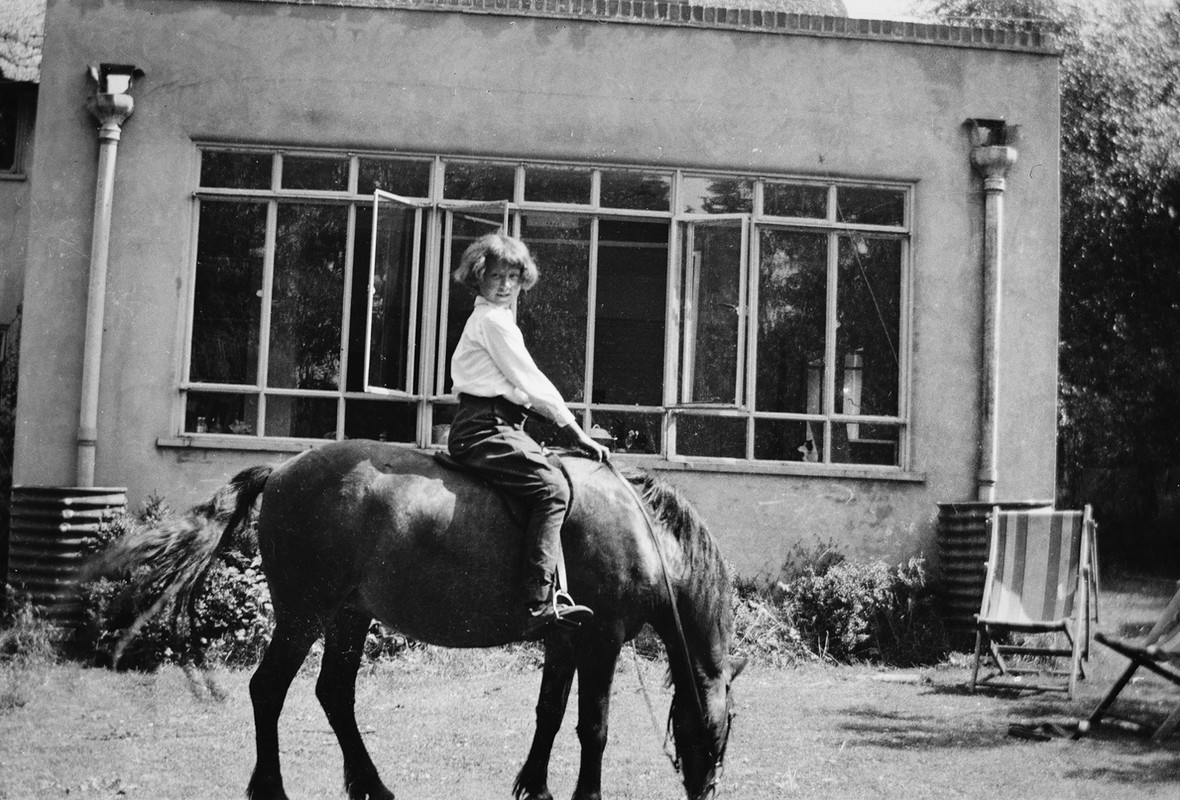

'Appletreewick' named after a village in the Yorkshire dales. Photo by Crispin Eurich.

This is how it was at Appletreewick, a world of its own. On the surface it was secure and safe but underneath teeming with subconscious feeling, which could be beautiful and dangerous by turns. It was hard for us to leave, but this was where our parents lived for over 60 years creating a mythic environment, which lives with us long after their death.

This inner world of our father comes over strongly in the best of his work. The early paintings are a sort of narrative seen through the lens of his childhood experiences, full of detail and clarity. They are popular with the public, maybe because there is nostalgia there, or maybe because we can get caught up into the story and fuse it with our own.

The war paintings are not an expression of the horrors of war, but more a statement of how things were. The nearest he got to allowing his feelings to surface was in “Survivors of a Torpedoed Ship” showing men clinging to an upturned boat, wrung out by their experiences, almost dead, awaiting rescue. The seagull is the only apparent sign of life. This painting was suppressed from public view as it was considered it might affect public morale, but in later years my father got letters from men saying: “That was me.” It was true.