Paintings that have influenced a young painter are not always a masterpiece.

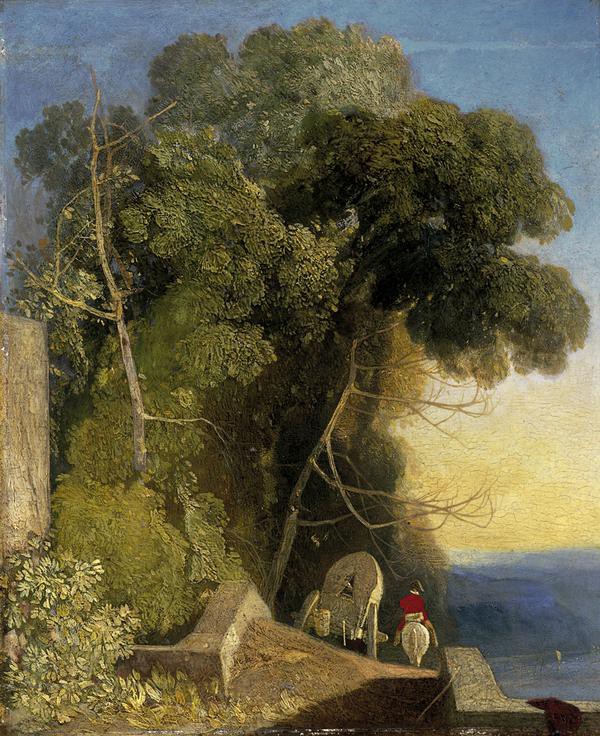

Those of us who lived outside London in the nineteen twenties had little opportunity of seeing original paintings, and the present day student would be astonished at the poor quality and limited range of the reproductions which were our fare. Hardly any French painting was known to us. The Italians were represented by a very few masters. The very first book on art ever given was on watercolour painting and oddly enough Cotman’s The Baggage Wagon was included in the black and white reproductions. Although Cotman resorted to all sorts of tricks to obtain the modeling of trees in watercolour I felt that the general richness of this work could only be executed in oil. The subject appealed to me.

'The Baggage Wagon' by John Sell Cotman (1782-1842)