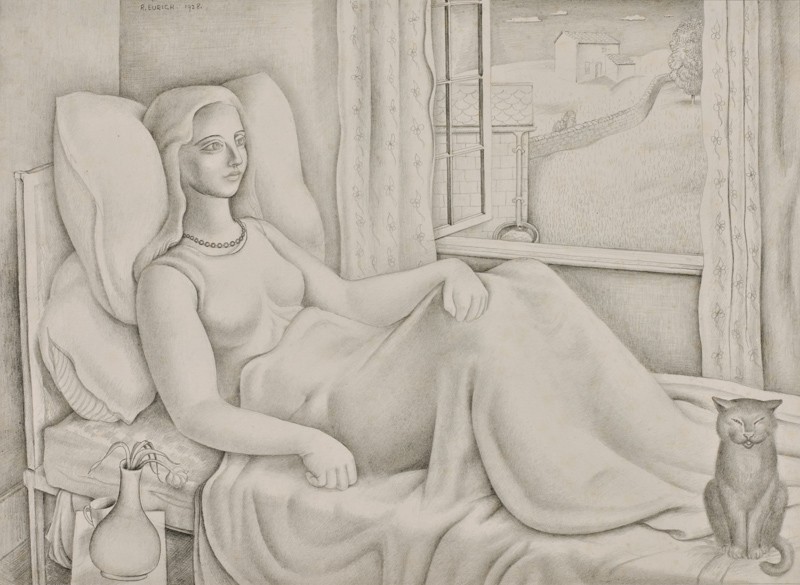

I arrived back in London in the autumn and as a final fling drew two large drawings, one of them must have been about four feet high, a single figure of a woman. The other was of two figures in which the shapes made by crossed limbs was explored.

Several friends who were curious to see what I had been up to in my retirement invited me to go to see them and others paid me a visit. A very gifted and charming woman sculptor and painter with whom I had become acquainted in Ilkley had come to London so as to try to get commissions and be nearer the centre of the artistic world. She invited me to her home from time to time to meet some of the people she had got to know as she thought they might be useful acquaintances for me. I quite enjoyed meeting some of them. They were entertaining and their conversation was something new to me and as long as I was left out of it and not expected to make cynical comments, I was content. I could never think of the words in which to answer a question. It always took me about a week to think of the correct reply by which time it was somewhat out of date. So one day at this house I was taken to task by my hostess. She was quite exasperated. She looked at me and asked me how old I was. I told her I was twenty-six. She went on to say that she couldn’t make me out. I looked like a boy of eighteen: I had no conversation: I made no attempt to follow up the introductions she had given me: I was awkward and (I am sure she was going to say ‘rude’) and no-one would suspect me of having any talent. This talent was my only virtue. She could not understand how I came to draw pictures full of amusing and comic ideas and yet be so stupid. I didn’t go to parties where I would get to know people who might be useful to me but instead was content to be friendly with socially inferior people who were no use to me, etc. etc.

I was astonished at this outburst and of course could give her no satisfactory answer concerning my behaviour. I think she overestimated my talent. If she had realised that I had no facility and that an apparently light hearted composition was the result of very close application and hard work she might have understood much that was incomprehensible. When she had a preview of my drawings she said that I would be a rich man after my show.

It was about now that I first made the acquaintance of the letters of Mozart and his father Leopold. These wonderful documents of an artist’s life and times have remained with me as an inspiration and example ever since. These, and the story of Handel’s fortitude and humanity, and John Constable’s very ordinary domestic life are in my opinion, the best reading for any student.

Meanwhile Mother had gone to a sanatorium in Somerset to try some new treatment and get a little sun during the winter. She told me in one of her long letters that the doctor in charge was very musical and as he was frequently in London would like to meet me. This meeting took place and he invited me to his sanatorium as his guest for a few days. He told me he had a clavichord as well as a grand piano, a gramophone and hundreds of records. The clavichord was the greatest draw of all the blandishments. I had never heard one but a description of the instrument and the various praises concerning its merits from Bach to Beethoven excited my curiosity.

The only thing it has in common with the organ is that it has a keyboard. The clavichord is the softest voiced instrument like the humming of bees. The organ is the loudest and most spectacular whereas the former is the most intimate and its tone is too gentle to accompany any other instrument. The organ has no ‘touch’ but the clavichord is ‘touch’, the varying pressure of the fingers affecting the quality of the sound produced, even to playing out of tune.

Mother was very depressed when I arrived and perhaps for the first time I realised what fortitude was necessary on her part to overcome the disease. It was winter now and she was in a small room by herself with a high mullioned window and no fireplace. It was just a part of what had been partitioned into several smaller ones. Before, when I visited her at other sanatoriums it had been summer and deck chairs out on the lawns with plenty of company seemed on a casual visit to be as pleasant as such a place could be. But now, far from home and all the activities she loved, all there was to employ her was knitting, writing letters and reading, the latter having its limitations as her eyes tired easily.