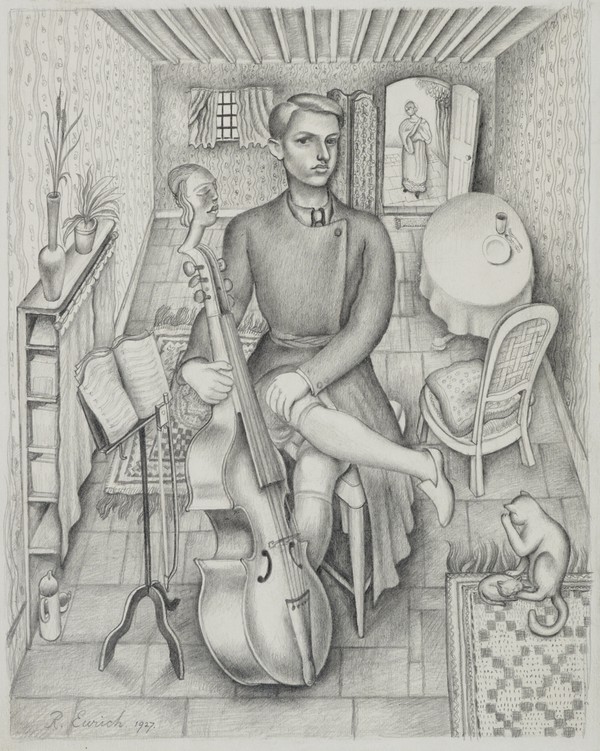

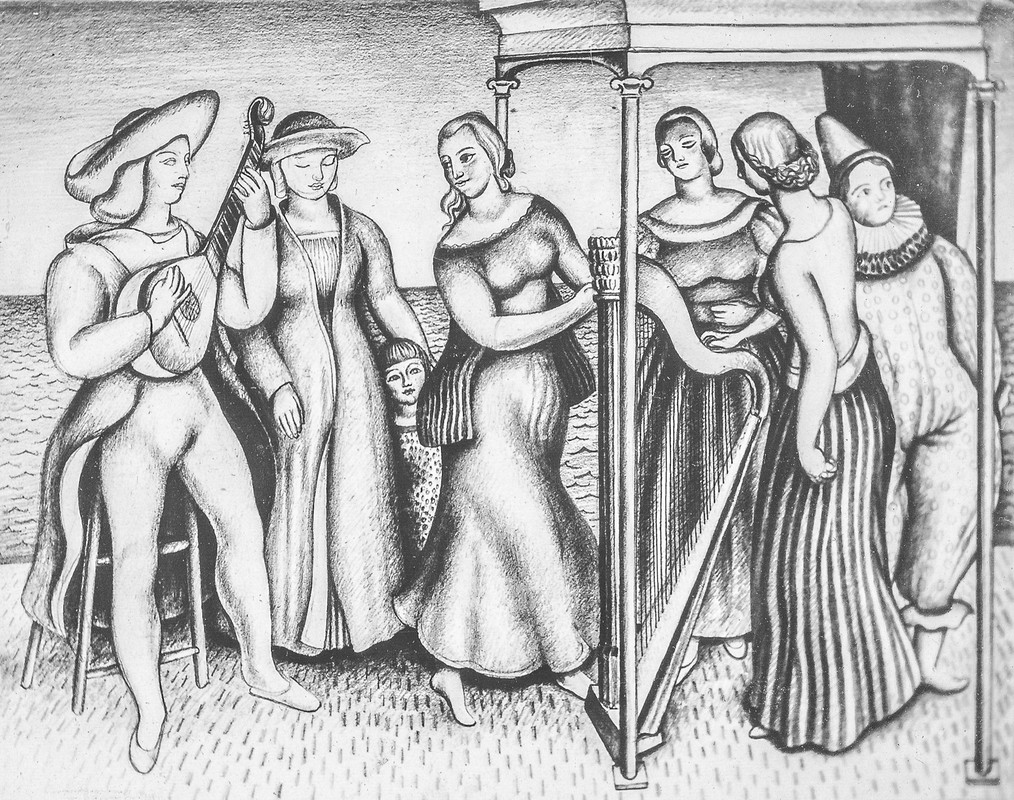

So I set to work to produce some more. They took me the best part of a week to execute, which is almost as long as a painting. The absurd method of pricing by size and medium was the only drawback to making these drawings from a material point of view. Four to eight guineas framed was the price of a drawing, while a small painting would be priced at ten to twenty guineas.

A friend of mine who was a secretary in the Treasury told me one day that a colleague of his had a large painting in his room which he thought I might like to see. He said he could arrange for me to go there so an appointment was made. Feeling rather shabby I presented myself at the entrance in Whitehall and was shown up. The painting was by Duncan Grant of an interior with David Garnett reading and Vanessa Bell painting. It must have been a six-footer. I was most impressed with the depth and richness of the work and was astonished when its owner said he couldn’t afford to keep it now he was married! I couldn’t place the reasoning behind the remark. He then said (out of politeness I thought) that he would like to come and see my work. I replied that it was very kind of him to say so and thought no more of it until my friend who escorted me to the entrance, remarked that I should take the old boy at his word and invite him some time soon.

So, when a few works had come back from exhibitions and there seemed to be something to show, I wrote inviting him to come and see me in my basement in Redcliffe gardens. He came and showed considerable interest but no desire to make an offer for anything. I remembered the remark about the state of matrimony and possession of pictures not being compatible. (He did however purchase some pictures later.) He said ‘I think Eddie Marsh ought to see these. I will send him along.’ I hadn’t the faintest idea where I had heard that name before, until I suddenly remembered that there was a painting by Mark Gertler on loan at the Tate Gallery giving the lender’s name as Edward Marsh. I probably admired Gertler’s paintings more than those of any other young man at that time and so I wondered whether the ‘sending of Eddie Marsh’ was just a bit of idle chat or whether it was genuine.

A day or two later a letter was pushed under my door addressed in an elegant handwriting. It was from Edward Marsh and he announced that he was coming to see me. I awaited the arrival with trepidation as the sordidness of my surroundings became for the first time evident to me. The entrance to my flat was down a flight of steps at the bottom of which all the dustbins and rubbish from the flats above street level were congregated. It was a filthy entrance, the resort of all the courting cats in the neighbourhood and stank accordingly. So when I went to the door in answer to a tap, I wondered very much what my visitor would be like. I was hardly prepared for the vision that greeted me. A rather stout man in a top hat, monocle, frock coat, rose and fern in buttonhole, kid gloves, spats and pinstriped trousers surmounted by a gorgeous waistcoat stood before me. He had evidently had some contretemps with an ashbin as its lid was rolling on the ground as though in agony and some dust from the ash was blowing about. ‘Eddie’ was ushered in coughing slightly through the dark passage, past the coal cellar into my living room. He announced in a high-pitched voice that everything was charming and when he asked a question in the same voice I had great difficulty in catching what he said and constantly had to ask for a repeat performance. I could see so I thought, that he was not particularly interested and wanted to get away without disappointing me.

He explained how his rooms were absolutely full and there was no space left for pictures, even the doors having paintings attached to them. I felt this was just another excuse for not buying anything but I found out afterwards that it was perfectly true. He then spotted a very small landscape in oil and asked me how much I wanted for it. This is always an embarrassing question, and I replied something about five pounds. He said he would take it if I could find some paper to put around it. He had got quite a lot of cobwebs on his gloves from the back of the canvas and was attempting to get rid of them, no easy matter. He made his adieu probably feeling that he had bought himself out of an awkward situation rather expensively.

So I was astonished to receive a letter from him a couple of days later saying he had been to the St. George’s Gallery in Hanover Square and had seen my drawings there. He went on to say that one of them was far superior to anything he had seen at my studio and he would have bought it only it was unfortunately already sold. So he had purchased the next best! This was news indeed. Things seemed to be on the move at last.

Father came down to London for a meeting and saw the place where I was living for the first time. He didn’t like it no doubt having Mother’s illness in mind, and suggested I should move. I was delighted to find an attic in Coleherne Road where I lived for the next five years. The attic next door was inhabited by Edwin Evans the music critic. He was president of the Camargo Society and great champion of Stravinsky. He would play snatches of Petrouschka from time to time on his piano and it made me feel less isolated.