During these months I had produced quite a number of paintings and it was decided that I should go back to London to try my luck.

Studios were difficult to come by and very expensive. It would seem that many of them were inhabited by people who were not artists, but liked to give parties and lie about on cushions and divans covered with exotic-looking draperies.

So I found myself in a kind of storeroom with a skylight. The room was so high that it was pointed out to me that if I could only turn it on one side it would be quite a nice place. It was dark and dirty and infested with mice. One of the first things I purchased was a metal safe to keep food in, otherwise I could not have kept any at all.

There was a basin with a tap and I cooked on a Primus stove. A camp bed, a chair and a table were my furniture, and I kept my clothes in a cabin trunk.

Here I painted two or three quite large canvases and I carried them round to dealers and exhibitions without success. I must have walked miles with the awkward things; one had to be very careful when approaching a street corner in case a gust of wind caught the canvases and blew you off the pavement into the traffic.

When I was in Bradford, Percy M. Turner who was a friend of Charles Rutherston came to visit the school and had seen some of my work. I went to see him at the Independent Gallery taking three paintings with me. He was talking to Roger Fry when I went in, so I took the opportunity to look at the paintings on the walls, and there to my astonishment was the thickly painted little Head of Choquet by Cézanne, which I had seen reproduced so many times. Also Vincent Van Gogh’s landscape of miles and miles of fields with a blue cart in one of them and hills in the distance. This one has become very well known through reproductions since then.

Percy Turner looked at my work and expressed himself as surprised that I wasn’t selling at all. He took one of the paintings and kept it several weeks. I thought that after that time had elapsed that I had better have it back. So I called at the Gallery and found two young men in charge, Percy Turner being away. I always found these dealers’ Lizards very offensive, and these were no exception to the rule. My picture was handed back as though some unclean object, without comment.

I wrote to another gallery that seemed to be exhibiting work by young artists, suggesting that if they were interested in paintings they might call on me. Oddly enough the proprietors came. They asked me why I had written that letter to which I gave the reply that I wanted to sell my work. They purchased a small one that I had painted when I was at the Slade but I heard no more from them as the gallery was given up shortly afterwards.

In 1927 the Daily Express organized a young artists’ exhibition. It was a remarkable show. Paul Nash and Mark Gertler had work there, and it was here I believe that John Armstrong first exhibited the fine tempera paintings he was doing at this time. I was fortunate in having two paintings hung and went to the private view.

I am still convinced when I walk into a gallery in which a picture of mine is hanging that I will spot it at once but I am always disillusioned, it never happens that way. So then one begins to negligently stroll around looking at the other paintings in an offhand way until you are suddenly confronted with a miserable work which bears some resemblance to the one which you thought, after much hard work, was one of the better efforts. But here it looks half its size, it is flattened out by the devastating light and almost everything that can be wrong with a picture is about as wrong as it can be. But the other paintings look all right so what is the matter?

One of my landscapes of Scotland was hung and a Mother and Child. The latter I had worked on for weeks, a number of friends had approved of it, and I was fondly under the impression that it was something between a Picasso and a Crivelli. It was rather badly skied in this exhibition, but I was quite horrified at its lack of unity and fervently hoped no one would notice it.

When the closing day arrived I called for the pictures, took them back to my studio and demolished the Mother and Child then and there. I wonder now whether I was over hasty and perhaps made a mistake, because since then so many of my paintings have affected me in the same way when I have seen them hung, and yet they have been noticed and even sold.

There is a popular belief that painters, when they have painted a picture are possessed only by a strong desire to show it to somebody, or better still exhibit it publicly. My belief is that nothing is further from the truth. Once a painting is finished that is the end of it, apart from the fact that if the artist wants to live and to paint other pictures he has to sell it. So he exhibits it and once he has learned the awful consequences of going to an exhibition where the work is hanging, he wisely keeps away. Sometimes there is a painting which is so much part of the artist, so much a slice out of his life, that when he first allows some intimate friend to see it and look at it, the natural inclination is to leave him alone with it, or even get someone else to introduce the work. It is possible to be more detached when the next problem is well on the way. But an artist is indeed fortunate if he has two or three friends who understand and encourage his work. Constable had one, Turner perhaps two. They were not critics or connoisseurs, but those despised people who in the popular phrase ‘knew what they liked.’ It is quite possible that if Archdeacon Fisher had not been the man ‘who knew a good thing when he saw it’, that many of Constable’s masterpieces would not have come into existence.

I became so worried about my work that I began to take more notice of what was going on in the art world than I had previously. There was an unfortunate craze for decoration or decorative painting. It was very much in evidence in all exhibitions and it was heralded by critics as being ‘real painting at last.’ I was unfortunately led up the garden path and set to work painting large canvases in the decorative manner which I found could be produced at a considerable speed. The impact of Matisse and Dufy was very much in evidence, and they certainly had the effect of making Turner and Constable and Rembrandt look a bit drab. The latter always commands respect because of his evident grasp of form. But it is more elusive in landscape painting, and Turner and Constable were under a cloud so thick that it was impossible to see their work.

I was introduced to a connoisseur who was so erudite I was terrified of him. There seemed to be so few artists who met with his approval that one was almost ashamed to mention Rembrandt or Michelangelo. They could so easily be dismissed with a wave of the hand and some comic turn of speech. The fact of the matter was that they did not fit into a theory. So it was with considerable anxiety that I put forward Turner as a possible candidate for approval. ‘What! Turner?’ he replied. ‘No geometry!’ I was crestfallen. But now Turner has been discovered again and it appears that geometry is one of his many excellences.

Now, looking at pictures meant going in to the West End and the Tate gallery. I always had to walk, as the fares could mount up and I had never got into the habit of taking buses and tube trains. Even when I was at the Slade I frequently walked the four miles from my lodgings. So, being much nearer to the museums in Kensington I began to go to them quite regularly on Sunday afternoons with John Bickerdike.

There is always the initial difficulty of deciding what to look at in museums which have so much to offer. Many people go in an aimless kind of way with the hope that something will hit them. Or perhaps they see someone else looking at something with evident interest, so they wonder what there is in that particular object worth looking at. Then they take a closer look themselves and if their minds are receptive, may find something of a revelation. There have been times when I have discovered with a friend some work of art tucked away in a corner which moved us so profoundly that no words passed between us. Just some slight look or gesture of acknowledgement and perfect understanding was enough, and the heightened tension made perception more acute. If one had been alone, this receptive state might never have occurred. On the other hand I have sometimes taken a friend to see the wonder and no spell was cast. There was no communication, all was flat and lifeless. It is a commonplace that a comedian can appear singularly unfunny when listened to by oneself alone. But also listening to music with a companion who by a glance one knows is not in a receptive state, can make a masterpiece appear unprofitable. The late Sir Desmond McCarthy once said in a talk on the radio that he thought he was receptive to painting because he could look at a picture for two minutes. He acknowledged that this might seem an outrageous statement, so he qualified it by suggesting that next time his listeners were in the National Gallery they should observe whether other viewers remained in front of a painting for as much as two minutes. I went to the National Gallery one evening, not with a view to testing this observation as I knew that Sir Desmond was correct, but to ascertain what other people looked at in paintings. It was getting dark and the lights were on. There were not many people in the galleries. So I took up my stance before Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne knowing that a crowd attracts others. Before long a man approached and stood looking at the same picture. I moved slightly to one side out of politeness. ‘Now’, I wondered, ‘What is he looking at?’ The focus of my eyes changed and I saw his reflection in the picture’s glass. I moved a little and so did he. I realized then that he was looking at my reflection. I thought to myself, if I stand where I cannot see his reflection then he would not be able to see mine. So a little skirmish ensued which was cut short by the shrill blast of a police whistle, all the lights went out and I groped my way towards the exit in a somewhat dazed state. It was closing time and I found myself in Trafalgar Square dodging the starlings.

One of the experiences I shall not forget was in the Indian Museum, which became ever increasingly our Sunday afternoon haunt. There one afternoon we saw a mysterious form standing (though it had no legs) in a dark corner. It was placed on a piece of newspaper on the floor. We took one look at it and then by that bond of consent I have already mentioned, we both went down on our knees and began examining it carefully. We felt it with our hands and the breadth and subtlety of the forms were breathtaking. We were interrupted by two attendants, who were no doubt contemplating throwing us out. Bickerdike said: ‘How much do you want for it?’ One of them promptly replied ‘Come back in a week’s time and we will see what we can do for you.’ After many visits we eventually found this superb torso of red sandstone standing on a plinth in majestic isolation. A short time after that a glass case was placed over it and a label appeared informing us it was ‘The Sanchi Torso.’ A few years later it appeared as a colour photo across two pages of an illustrated weekly described as a great find and one of the world’s great masterpieces.

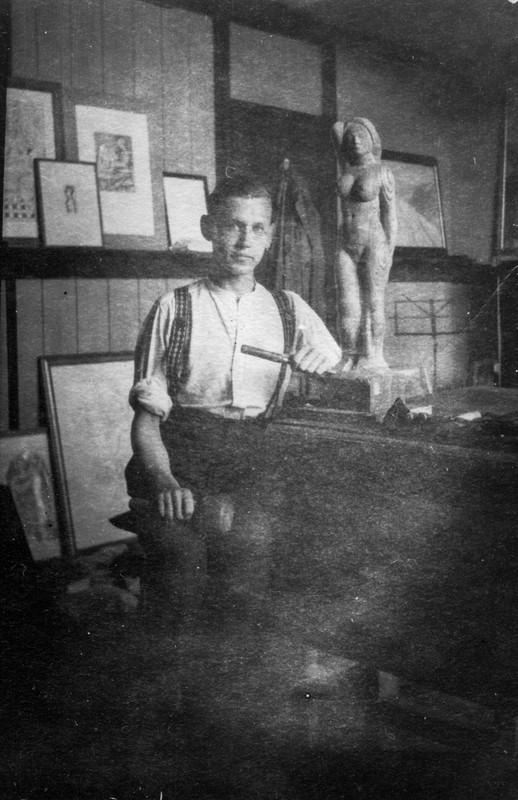

I became increasingly interested in sculpture and spent some time carving in wood, including a two-foot figure and some puppet heads.