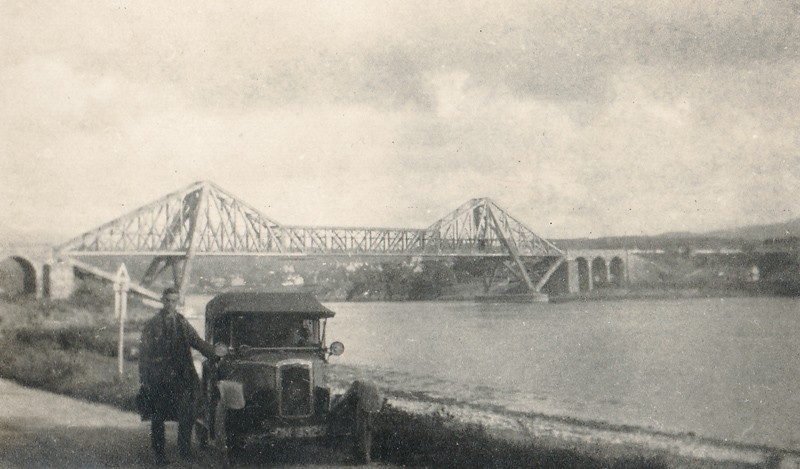

Richard beside his friend's car at the Connel Bridge north of Oban on the west coast of Scotland, 1926.

Richard beside his friend's car at the Connel Bridge north of Oban on the west coast of Scotland, 1926.

I had been fortunate enough to win a prize for life drawing at the Slade and with it I purchased painting materials, which I hoped would last for the next year.

I started exhibiting in London while I was still a student, and actually had a painting hung in the London Group. The New English Art Club was considered to be the Slade Mecca, but I was not successful there – once, on one of my rejected paintings, I found a little unsigned note. It was wedged into the canvas back. It just said ‘Sorry, try again.’ I don’t know who was responsible on the selection jury for this kind thought, it may have been Tonks himself but I don’t think the writing was in his hand.

During the Summer I painted at home in Ilkley and produced what I considered to be my best work to date, but none of the London Exhibitions would take them. They were exhibited in Bradford where they attracted some notice in the press. One of the consequences of this was a short article about me and my painting in a well-known art magazine. Unfortunately a friend of mine allowed the writer of the article to quote from a letter I had written in which I said I was ‘trying to unlearn what I had learned in school’…. A typically foolish remark which students who are trying their wings like to make.

It was some months later when I was back in London that I happened to be walking over the Albert Bridge when I saw a familiar tall figure approaching from the opposite direction with that peculiar gait which suggested a stiff neck and boots with soles of lead. I wondered as we drew nearer to each other whether Tonks would remember me. I think I even neglected to say goodbye to him when I left the Slade. But he stopped to speak to me saying that he had seen the article about me, and felt that some people might be a little bit hurt by it. I told him that I was very sorry about it and explained the circumstances of the quotation. He understood perfectly and we parted on good terms. I imagined afterwards newspaper headings: ‘Fight on Albert Bridge’, ‘Professor and Student in Mortal Combat’, ‘Body in the Thames.’

I never saw him again but I received a letter from him concerning my drawings a couple of years later saying he thought I ought to go in for engraving.

I heard from a fellow student who stayed on for another year that a special prize was being offered personally by the Professor for drawing from life. The nature of the prize was being kept secret, and I gathered there was a certain amount of speculation concerning it.

A later letter announced that my friend had won the great prize – two large volumes of reproductions of Ingres! We had decided among ourselves that Tonks’ idol was no good, so the great prize was a bit of a disappointment. ‘However’, my friend ended philosophically ‘it was perhaps a good thing that I got the prize, if they had fallen into other hands they might have done untold harm.’ The letter had a postscript in the shape of a beautiful imitation of a Picasso drawing.

Among the paintings I did just after I left the Slade was a self-portrait, which was my first attempt at painting a head. I was then offered a commission to paint the portrait of a little girl. I went to the house and Auntie read Through the Looking Glass to her, but longer than one hour she would not sit. In that time I had painted quite a good head, with arms and hands indicated. I tried to tidy it up a bit but probably ruined its freshness and vitality. A great friend of mine offered himself as a model if I wanted some practice so I painted a life-size head and shoulders of him.

Self Portrait (1926)

Learning his craft: a strong portrait of his 23-year old self

One day a friend wrote to say he was planning to go camping in Scotland with his car, would I care to come? The only qualification being that I could erect a tent. I replied that I would be delighted and could and would put up a tent.

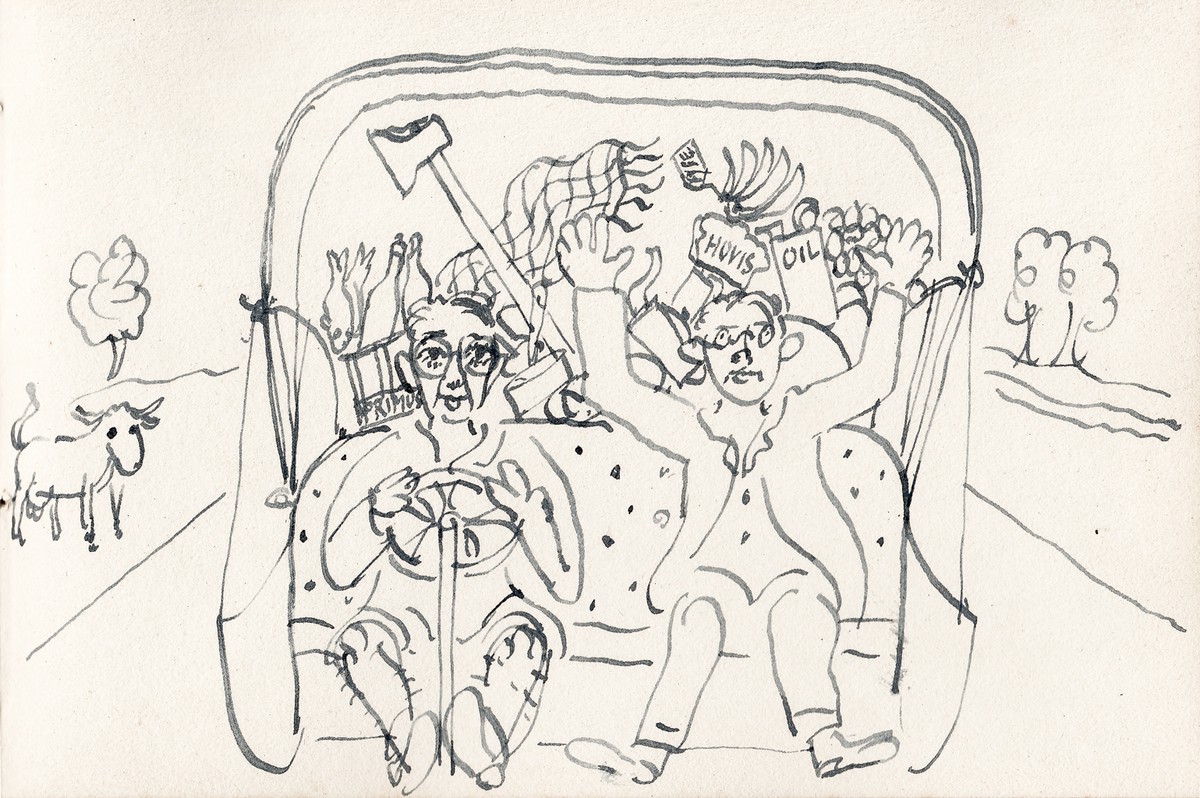

The day arrived and so did the friend with a runabout car of ancient vintage. He looked at my very modest luggage which of course included my sketching box. He said he thought there wouldn’t be room for the box, could we send it on to some station in Scotland? I was amazed, no room?! Whatever kind of car was it? I went and looked – well, I understood when I saw in the back of the vehicle tents, pots and pans, a forester’s axe and what looked like spare parts for every department of the car and tools for dismantling and reassembling. So my sketching box was sent to Loch Lomond.

"Every time we went downhill or stopped suddenly I had to hold my arms up above my head to stop the inevitable avalanche of pans and food and kettles." Illustration from a 1932 letter written by Richard to his future wife Mavis describing to her his 1926 camping trip to Scotland.

Before we had gone many miles I began to have my misgivings and wished myself at home. Every time we went downhill or stopped suddenly I had to hold my arms up above my head to stop the inevitable avalanche of pans and food and kettles. The hood always had to be up to keep these articles within bounds when travelling on the level. My friend’s driving too was most unreliable. He hugged the steering wheel with both hands meeting at the top, so that every time his body swayed the car responded sensitively by lurching across the road. As soon as he became aware of this from hoots of approaching cars, he wrenched the wheel so violently that we nearly shot up the opposite bank. The engine too was temperamental and showed a marked tendency to stall in traffic. There was no self-starter so I had to disentangle myself from camping impedimenta, clamber out and go to work laboriously with the handle. When we were hill climbing the gear had a tendency to slip into reverse or else the lever would go out of gear and we would start running backwards. The brakes were inefficient so I had to seize a large stone from among the pots and pans, leap out and ram it under a wheel. While I was doing this, my friend would succeed in his efforts to engage gear and start off in a forward direction with a sudden jerk and screech and I would have to race after him and scramble aboard.

On one occasion I thought our last hour had come. We had somehow managed to get on one of the primitive car ferries running across a loch. When we arrived at the other side a couple of flimsy boards were placed for us to run down onto a slipway which the ferryboat moored against. The angle of the slipway naturally made one of the duckboards lower than the other so that as the car ran down them it assumed a list of dangerous proportions. But this was not the only difficulty, for on arriving on the inclined slipway, the car had to be violently turned at right angles and run upwards to safety and the road above. So we charged down and then swung up the rough surface and of course the engine coughed having cooled down on the voyage, and conked out. The car started to slide backwards into the depths of the loch. I vaulted out and got my foot under the rear wheel. I was fortunately wearing mountaineering boots as I had been assured, quite correctly, that there was no room for a change of footwear. The ferryman had to come and start the engine up and the car shot up the incline nearly burying him and leaving me half crippled standing in the water. I was so relieved at our narrow escape that I hardly noticed that I was wet through. My fellow camper, seeming blissfully unaware that anything out of the ordinary had occurred waited for me to join him, and amid curses and other sounds of derision we shot off on our way.

I found out on our first night that my qualification for putting up a tent was not an idle one. My friend hammered pegs into the ground with an enormous mallet in a most un-geometrical pattern which bore no relation to the ground plan of the tent. So I had to take charge. I also found that housekeeping was not his forte, and cooking and washing up, particularly the latter, always brought on an urgent desire to take the car to pieces.

The weather was very bad indeed and the further north we got the colder it became especially at night. I retrieved my paint box at the station to which it had been sent and I began painting Ben Lomond from above Loch Sloy where there is now a power plant I believe.

Most nights were wet. The little tent was not waterproof and I began to get rheumatic. But on the only fine day we had, we climbed up the 2,800 feet of Ben Sgulaird from which I made drawings of the vast barren slopes of Glen Etive, with the great crags of Ben Vair and Ben Cruachan dominating the valley of Glen Creran. I had never seen anything so impressive before. The clouds were plentiful but high and the contours and shapes of the hills were thrown into relief by their shadows moving across them.

Scotland - mountain pass (1926)

Scottish mountains with their heads in the clouds

One night we put off looking for a camping site till it was nearly dark and we finally found an inviting-looking gate which appeared to be miles from anywhere. We pushed it open, ran the car inside and pitched the tent. It was the driest night we had and we were enjoying breakfast when a head was thrust into the tent and a Scots voice demanded whether we had permission to camp there. We were rather surprised as we seemed to be in such a lonely spot but we said ‘no’. ‘The Laird will be down to see ye’ was his final announcement and off he went. So we waited and eventually a real Laird came stumping over the mound above our camping ground looking like a giant on the skyline. He was bowlegged, kilted and bonneted; in fact he was a music hall Laird all right, full of bad temper and noise. My fellow camper thought perhaps he had better go and meet him so he put on his sunglasses, a strategic stroke I thought… there is nothing so disconcerting as talking to a person in dark glasses…. and went to encounter this Goliath. I don’t quite know what went on except a certain amount of threats and abuse. My friend innocently offered half a crown for any damage we might have done. After that we had to clear off quick. The Laird stumped through the gate and out onto the road apparently going in the direction of the village, which we gathered was farther on. We piled the gear into the car, negotiated the gate and started off in the same direction. For some reason there seemed to be much more traffic on the road than usual and we overtook our Laird just as a stream of cars came in the opposite direction. The road was rather narrow and we had to swerve almost into the hedge and the luckless Laird had to side step and make himself as thin as possible. Add a gutter full of muddy water, which our wheels passed through to the discomfiture of the Laird and our satisfaction was complete.

The next night was very wet and we camped in Glencoe of all places. We seemed to be surrounded by precipitous rock formations and somehow or other I managed to make several drawings of them. We put up the tent as best we could and crawled into it. I was getting increasingly rheumatic and hardly slept. When daylight came we found we were about two inches under water on an island with rushing streams all around us. Everything was damp and clammy if not really wet. It was cold, and lack of exercise had made me so stiff and low in vitality that I thought I had better go home. So we went on to Fort William where I could get a train.

The clouds were low over Ben Nevis. The forms vanishing upwards into these clouds became the subject of a painting when I got home. My last impression of Scotland on this tour was of a group of Highlanders in full dress with busbies and pipes swinging down the road. They were preparing for the Highland Games. The gallant feeling they gave was very different from the lone pipers we saw stalking over the moors playing old airs, the thin penetrating tones rising and falling as they moved, the gulls suddenly appearing out of the mist and wheeling away again. The archaic quality of the music and the linking of tunes by the drones made it seem as if these men had been playing there for centuries, moving sometimes in and sometimes out of earshot.