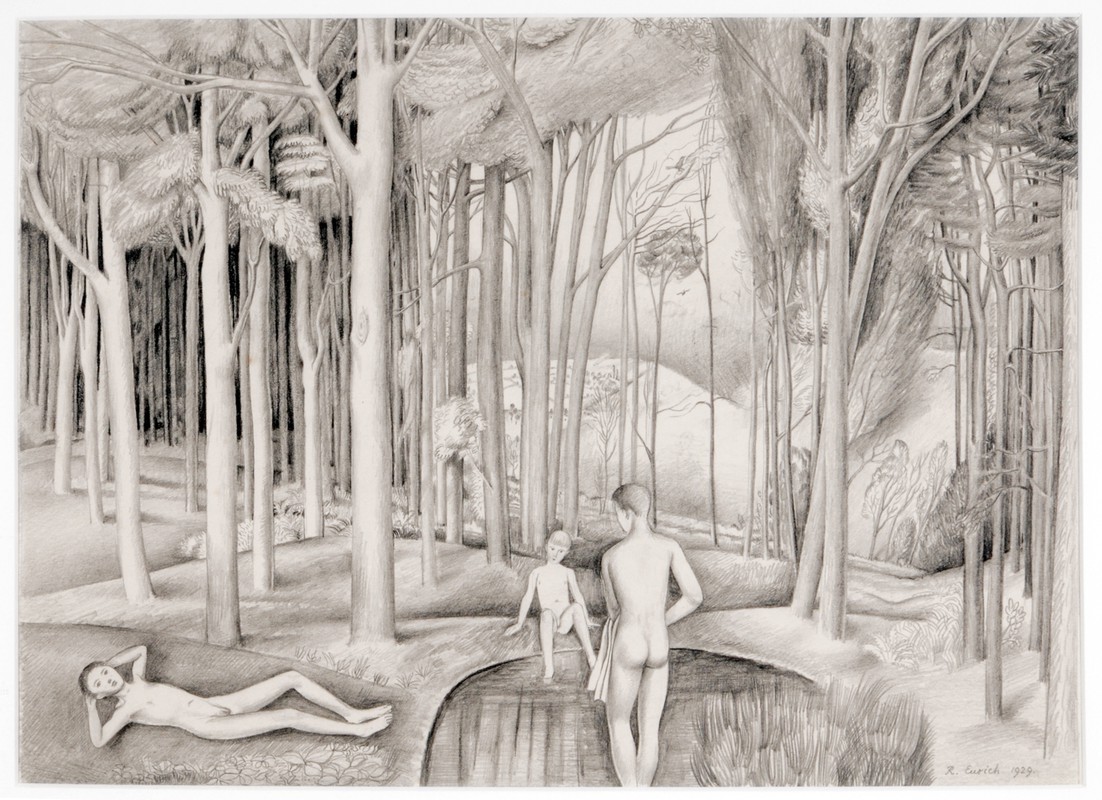

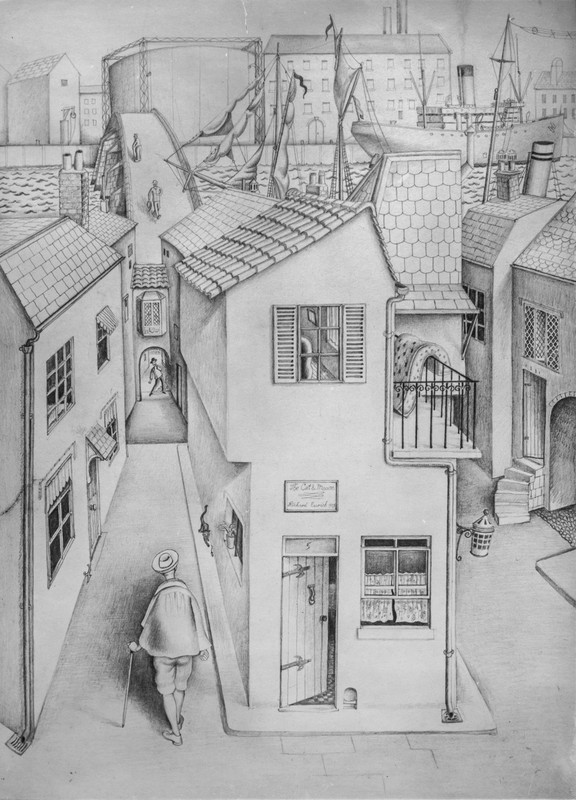

The Cat and Mouse (1929)

‘The Cat and Mouse’…could almost be an inn name as well as a real cat and mouse

Then I looked down the long passage which led to the Gallery’s premises at the back. There was a glass door at the far end. On opening it you usually fell down a step you didn’t know was there and faced a pompous secretary, at a distinct disadvantage. I couldn’t see that there was anyone in the place at all. It was about lunch time. My friend at the Treasury had said he would come at this time so I waited until he arrived and then sheepishly walked down the passage with him. We tried our strength on the panelled door, nearly broke our ankles on the step and gazed round the room. The Times had published a good notice and the secretary remarked that in the old days a notice like that could have brought people to the gallery in hundreds. Someone else pushed the door open but it was an artist who wasn’t looking at the pictures, only getting the dealers to know his face. One or two friends popped in saying how nice the show looked without having looked at all.

Then a stately lady in black came in (they never seem to trip up over an unexpected step) and floated towards me explaining that she was Mrs --- who had condescended to come as I was a friend of one of her late parishioners. I had been warned that she was very wealthy and might be persuaded to purchase a drawing. So I looked at her hopefully but didn’t get much encouragement. She glanced round and then seemed to shiver slightly remarking that she thought people wouldn’t want to buy black and white work in November, it was colour they wanted at this time of year. She shook hands with me again in a chilly fashion and I didn’t have to hold the door open for her as I noticed the young cockney, who was the odd job man about the gallery, on the other side of the glass panelling doing his stuff with an exaggerated flourish. So I had succeeded in frightening my first customer off.