Coast Scene with Rainbow (1952-53)

None of Richard’s holiday paintings survive but this ‘Coast Scene with Rainbow’ of 1953, surely harks back to his excitement at the first sight of Whitby that day

I was coming through the town one November morning, after practising the organ at All Saints Church, when excited paper boys came running down the streets. Their shouts were soon drowned in the shouts of soldiers who threw their caps into the air, and other people who eagerly snatched papers and there read the headlines that an armistice had been declared at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. So the war was over at last. Mr. Stott could come back and I could resume my lessons with him. But it also began to turn some people’s minds to summer holidays again at the seaside. And so it came about that Mr. Pearson having made arrangements for taking a cottage at Sandsend near Whitby, invited me to go for part of the time to paint 'and learn some strange ways of the Bohemians'.

Mrs Pearson and the two children had been installed in the cottage for some time before Mr. Pearson and I made our way there by train. I remember how his presence in the compartment gave me an added awareness of things as I sensed he was observant and watchful. I noticed the peculiarities of our travelling companions as I had never noticed them before. There was the fussy woman who at every station got hold of the Guard to make sure that all her eleven bags and other packages were safe. Mr. Pearson said he knew she would be like that because her nails were dirty! And then we compared notes about the fine lines round the mouth of a man sitting opposite us. A good model for a hero, suggested Mr. Pearson but, as he remarked later: 'When he took his hat off he was nothing'.

Coast Scene with Rainbow (1952-53)

None of Richard’s holiday paintings survive but this ‘Coast Scene with Rainbow’ of 1953, surely harks back to his excitement at the first sight of Whitby that day

The glimpse of the sea at Whitby and then from the train running along the cliffs to Sandsend was the climax of the feeling that the chains of the war and school had been thrown off. That line of cargo boats on the horizon which I was to live with for the next month with a telescope at the ready for any unusual feature, filled me with an inner joy which is so difficult to explain. I never tired of looking out to sea from that window as I later never tired of sitting on Chesil Beach by the hour together.

After we had a Yorkshire high tea, Mrs Pearson brought me the paintings she had been doing. It was a revelation to me to see work in progress like this and I could hardly wait till morning when I would take out my little drawing books and paint box and try my hand. I went for an evening stroll with Mr. Pearson on which he talked in a contemplative way about the scenery and the changing light. Anyone we met he would observe closely without apparently staring at them and I soon found myself doing the same. Sometimes he would mention someone we had passed at the next meal time and it soon became evident that our observations were frequently at different levels. He once said 'Just fancy anyone wanting to marry a girl with a face like that!' I said, innocently, 'but does some man want to?' He replied 'Yes, she was wearing an engagement ring'.

I soon found that painting out of doors has many disadvantages. The light is strong, one can be besieged by flies and worst of all, by nosey passers-by. These last drove me frantic and the last straw was when a man looking like a hairdresser with a waxed moustache came and sat beside me even though I had deliberately got my back to a sea wall, and began explaining how I ought to go about the job of painting. When he saw that I was not particularly impressed by his ideas he told me he was a professional artist and began using the term 'we' constantly: 'we' do it this way. At length he opened a bag and brought out some small watercolours which even I with my small experience recognised as the meanest kind of pretty calendar work. He placed them on my easel for me to look at. I didn’t know what to say except that it was time I was getting back to dinner. He packed up and wandered off along the sands, a rather pathetic and lonely figure, apparently looking for a customer rather than a motif.

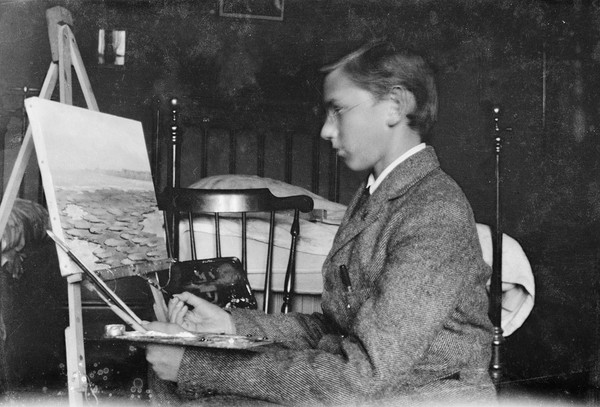

Richard paining in 1919. The view looks a bit like Sandsend Ness near the old quarries. Richard destroyed most of his paintings from this time.

I spent four of the happiest weeks imaginable painting about seventy small water colours and two oil paintings, never losing sight of the sea during the whole time. I couldn’t bear to go away from it. It was like a magnet constantly pulling me and the sound of the surf drifting through my sleep was spacious and soothing.

We talked, or I listened to talk, as other visitors including another painter came to stay in that small house. Mr. Pearson remarked to me 'Your Father will certainly be too sensible to allow you to become a painter' but somehow it didn’t ring quite true. Why was he encouraging me? Why did he say I would be able to paint so much better than he could someday? Looking at my early work I can only wonder that anyone could possible think it promising.