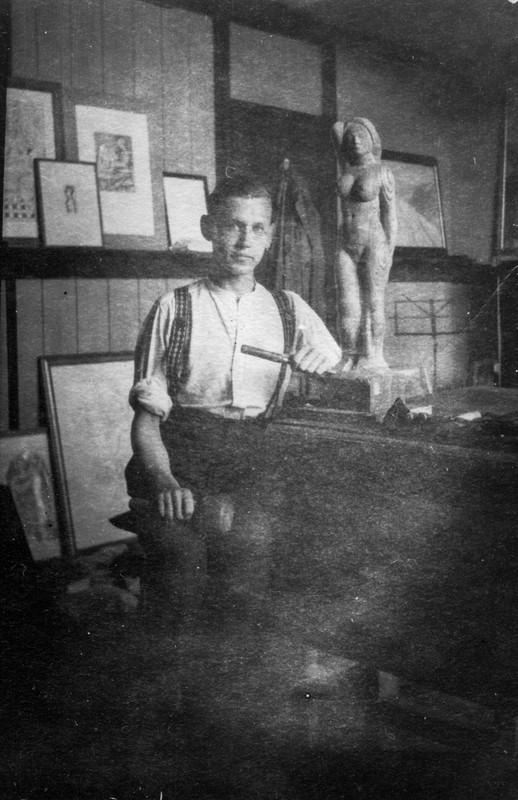

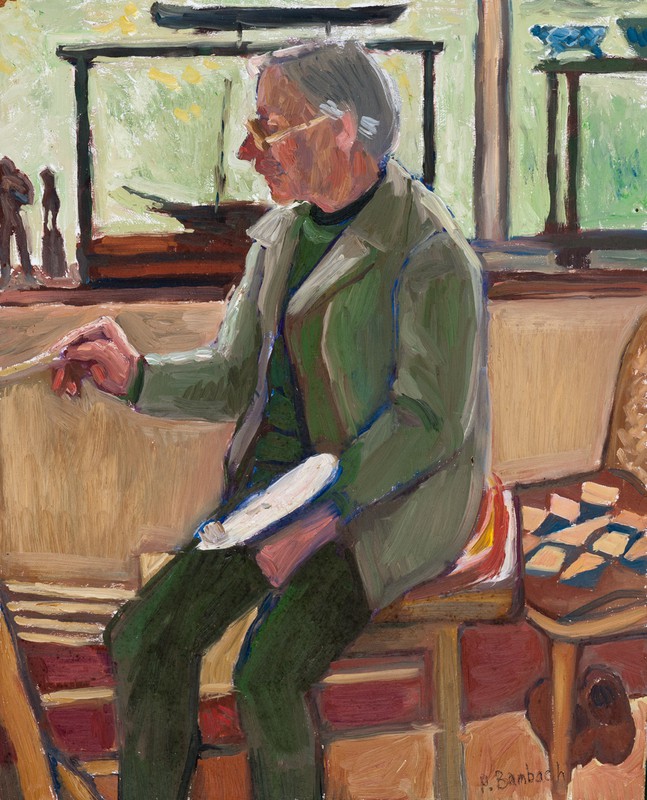

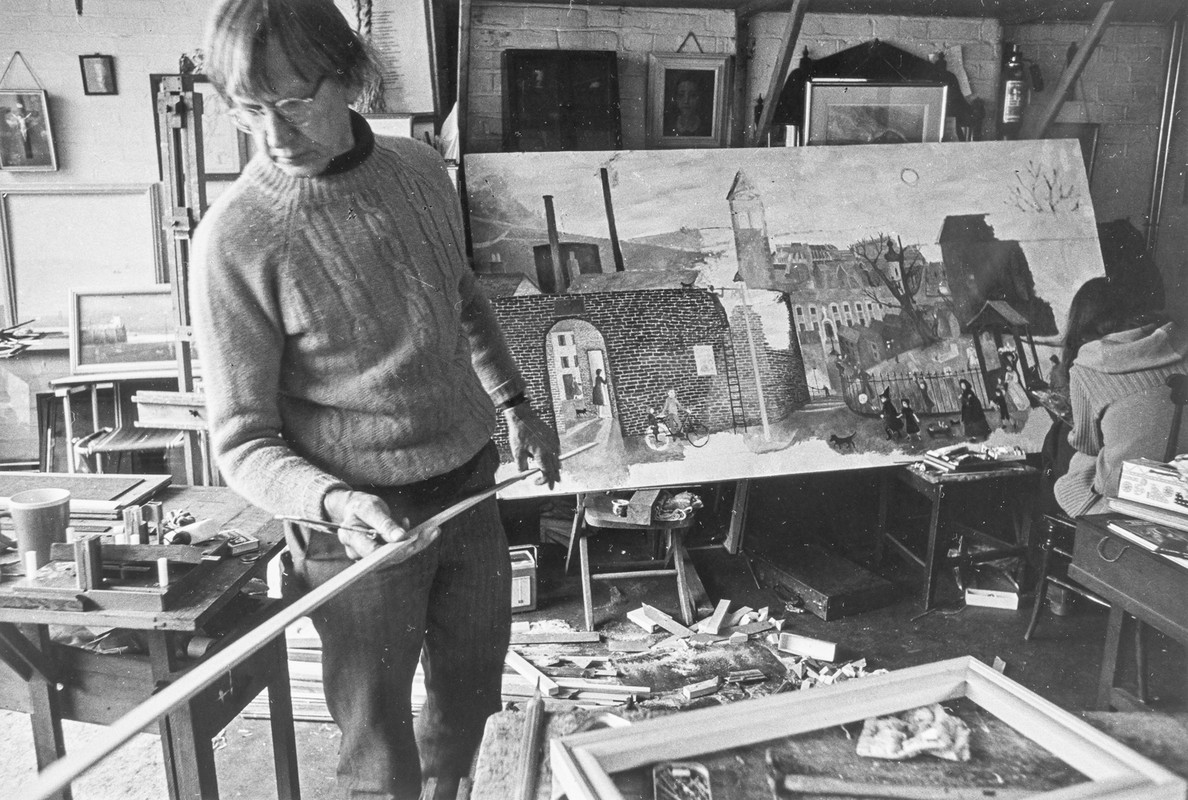

In September 1934, Mavis and Richard married. They built a house cheaply in the New Forest. Richard used a shed in the garden as his studio until 1950. He delivered all his paintings to the Redfern Gallery by placing them on the roof of their small Austin and driving them up to London.

Richard's daughter Caroline memories:

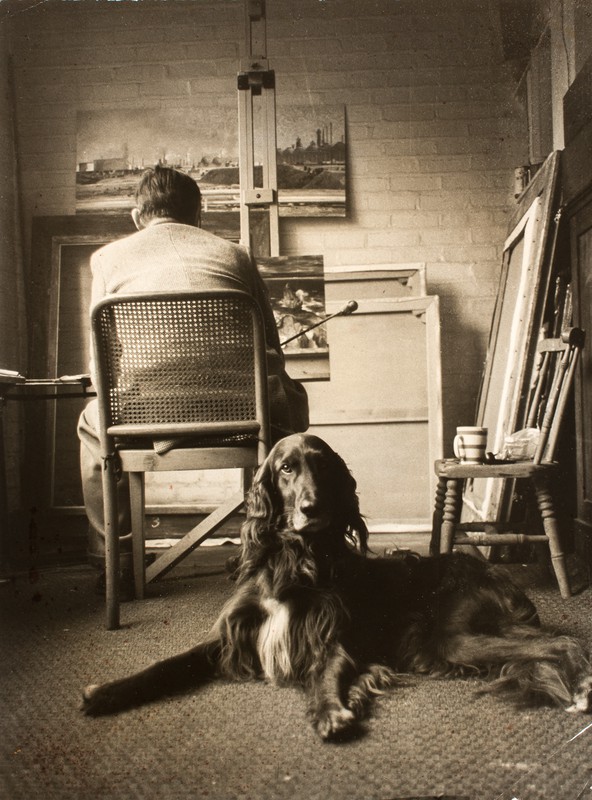

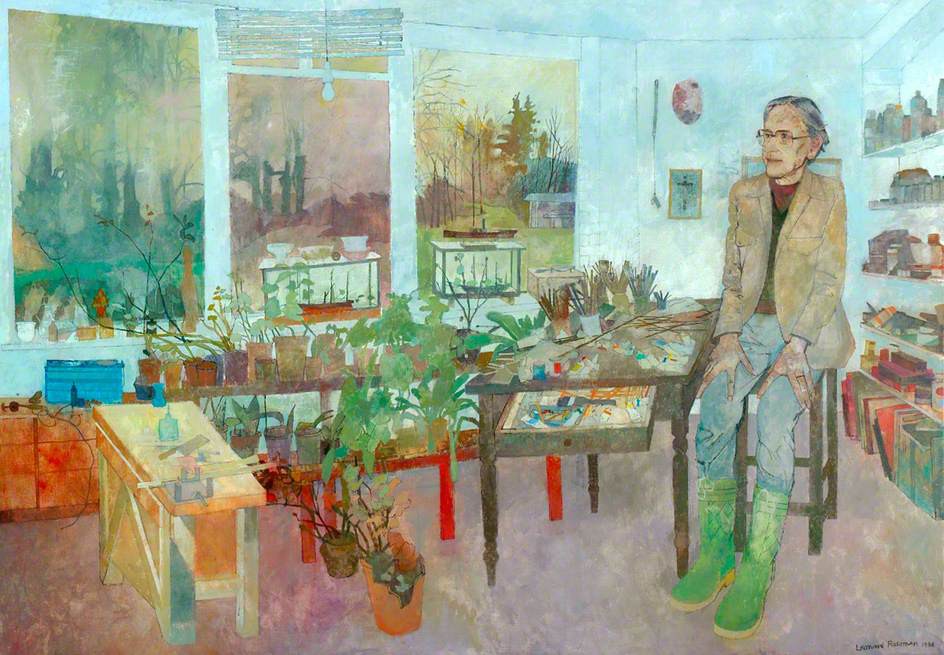

The White Hut seems to be a bit of a mystery as there are no photos of it. I remember crossing the garden to it, and climbing up a huge step to get in. It had large windows down one side, and was fairly empty to allow Dad to walk back from the easel.

It must have been very cold in there, particularly in the winter of 1947. It was heated by a couple of old fashioned Aladdin oil stoves, filled with pink paraffin, their glow reaching up through a pattern of holes in the lid. They were moved around with their woven wire handles. It was in this studio that he painted all the War pictures, and other great paintings besides. After the move to the new studio, the White hut was left to moulder, with plants growing up through its floor, and trees reaching over its roof. It turned into a dumping ground, but never actually fell down. It became just a memory.

Richard's nephew, Robin, came to Appletreewick in 1937 to see the Queen Mary in dock. Richard had helped to make a toy theatre for Robin.

Robin remembers:

"Sleeping by myself in a bed in the studio, I was given a torch in case I woke up in the night. However, I used it mostly to gaze at the wonderful pictures of ships and their rigging in one of Richard’s books. On my last morning I got up early to check whether the paint on the theatre had dried. When I told Richard that I had, he said “Have you been putting your paws all over it ?”